We almost kept going when we reached Spokane. Often I have wondered what might have turned out differently if we had.

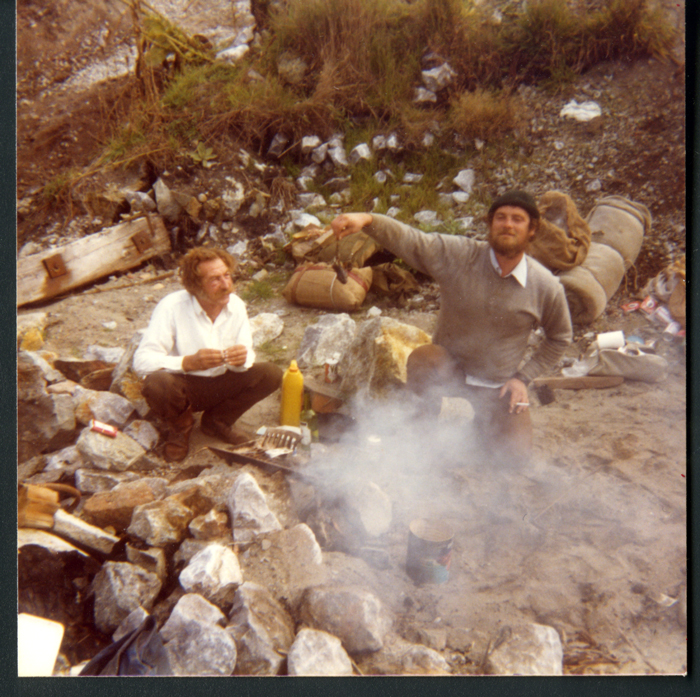

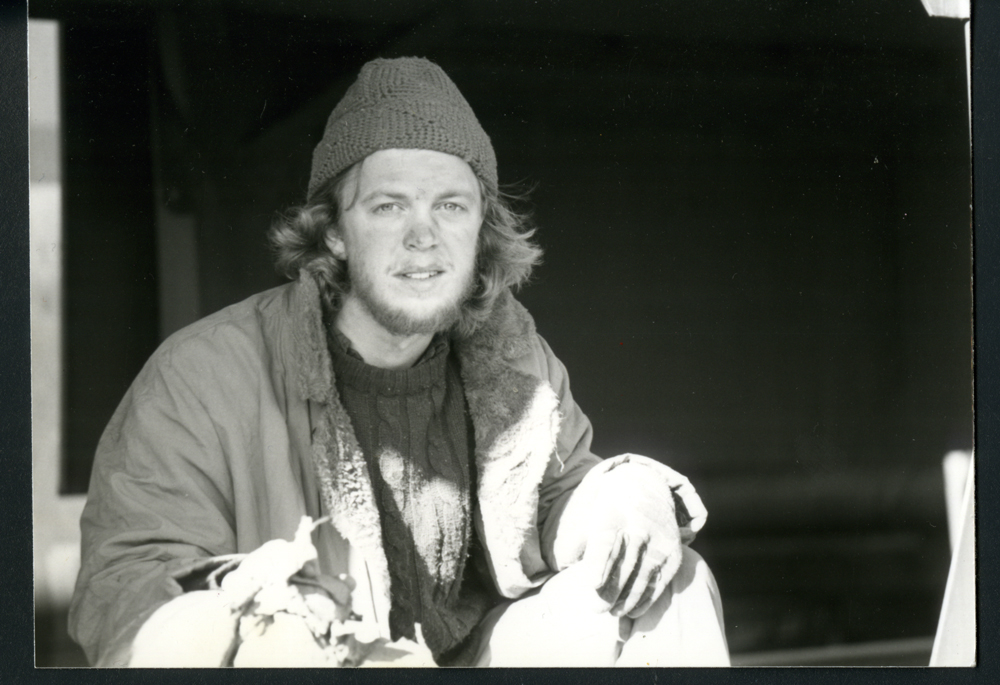

The idea of stopping in Spokane to work a day or two had been discussed since Fargo. The St. Vincent de Paul charity store there employed transients, paying them partly in cash and partly in the necessities of life: food, clothing, showers. Sleeping bags, in particular, were the currency Pete and BB hoped to receive, for though they each slept in two, one inserted inside the other, often wearing all their clothes, the bags were too old and thin for the autumn nights ahead.

But just a few steps off the train, BB stopped. “Wait a minute,” he said. “It’s Friday night. Tomorrow’s the weekend, and St. Vinnie’s ain’t open on the weekend. We’d have to wait till Monday.”

“Forget it, then,” said Pete. “Let’s keep on going.”

They had already turned around when I spoke up. It was Thursday night, I asserted, and tried to prove it to them by count¬ing back the days since the last weekend. But both of them refused to listen. Just then, however, a brakeman swung out from between two cars, not far from us, and I posed the question to him.

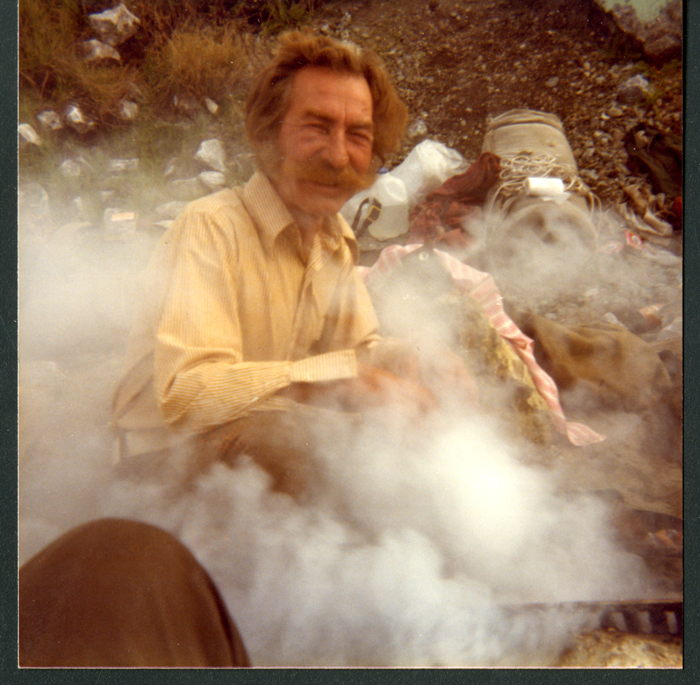

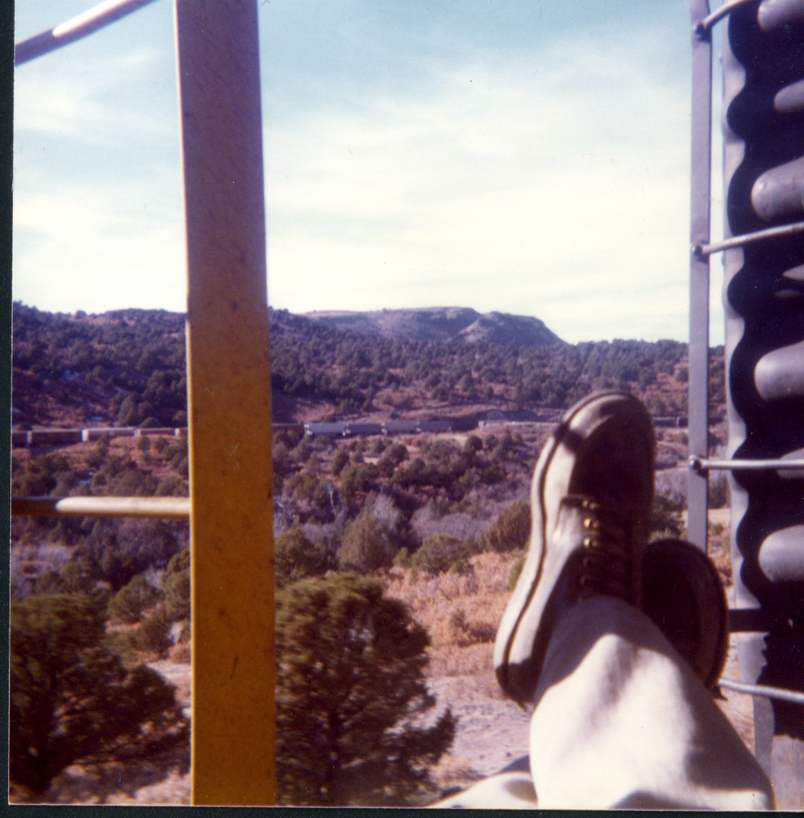

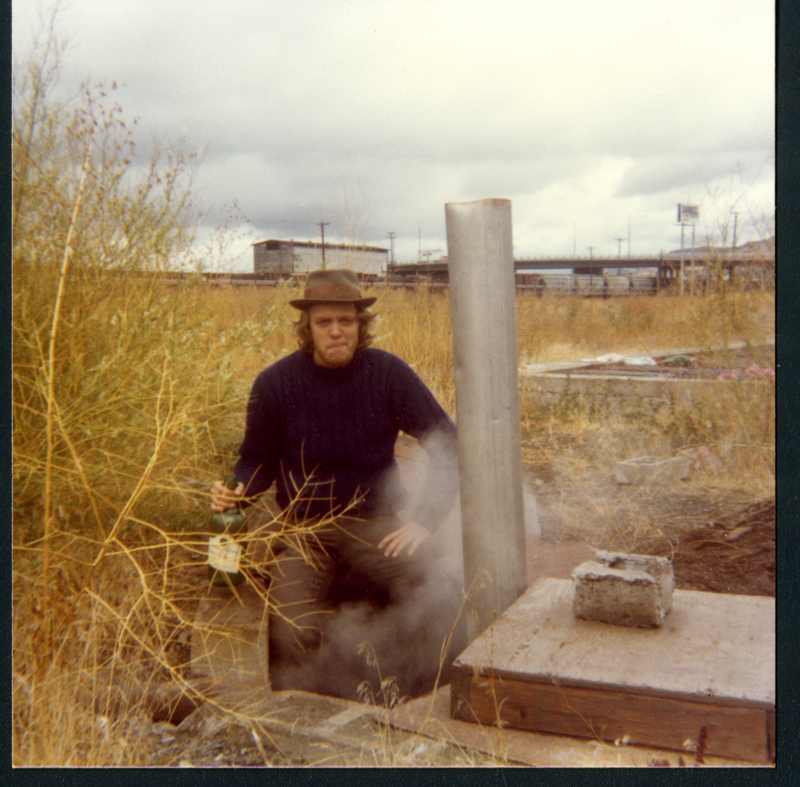

“‘Course it’s Thursday,” he said, laughing. BB and Pete were humorless. Silently they changed directions again, and we arrived at a weedpatch not far from where they had jungled up just a few weeks before. The tramps had been traveling so much that they were the victims of their own kind of if-it’s-Tuesday-this-must-be-Belgium syndrome

I was up at dawn. Arrive at St. Vinnie’s much later than that, BB said, and they might already have all the guys they needed. Because of his ever worsening wound, Pete would not work; instead, I would donate the bedroll I earned to him, since I already had the best bedroll of the three, and BB would keep the one he earned. We were, after all, partners, and among partners, as Pete had said, it was “all for one and one for all.”

But BB, strangely, lingered over his coffee, and then spent a lot of time helping Pete wrap his hand in a clean bandage “borrowed” from the first aid kit of a caboose. “You better get goin’,” he said. “I’ll finish this and be right over.”

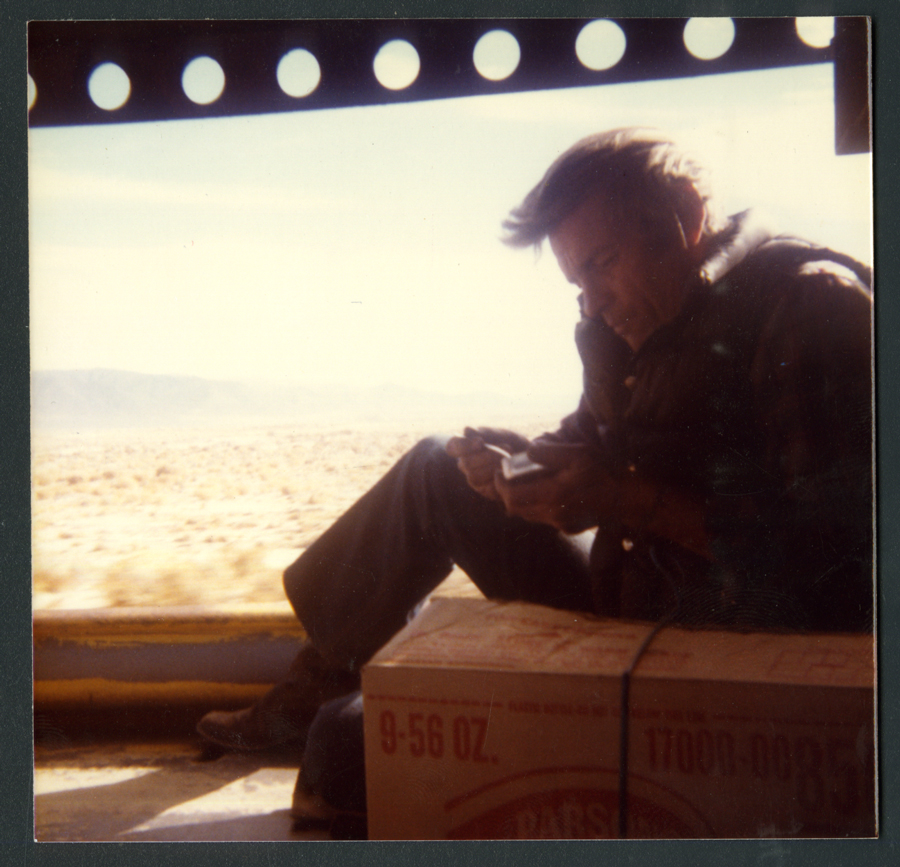

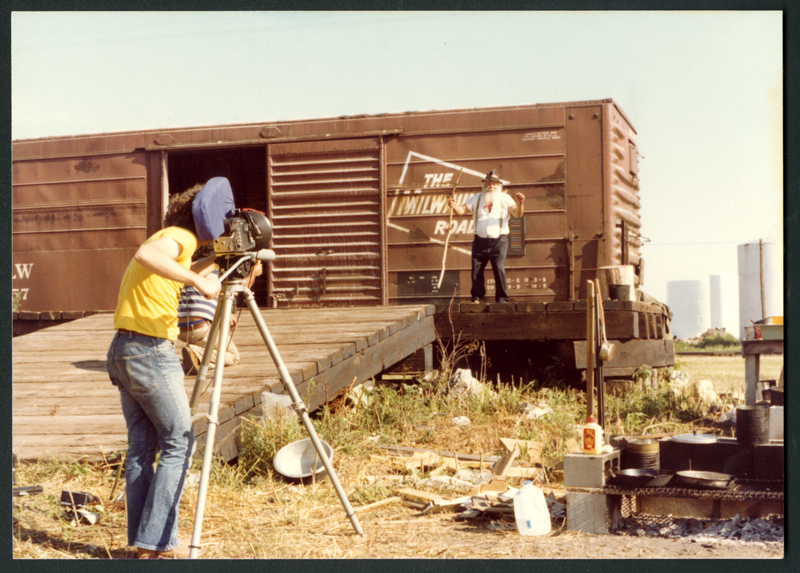

The work involved a lot of loading trucks and moving furniture. I was somewhat annoyed as the day progressed and BB failed to show, but other things kept my mind off it. One was the arrival of a police car and paramedics at the loading dock of a plant across the street. “Old Willy’s been hurt,” I heard one of the workers tell another. It seemed that Willy, a well known personage around the yards, often slept under the dock. Apparently, the night before an eight by eight inch wooden beam had fallen on him while he slept, pinning him and fracturing his ankle. It was midday now, and he had just been discovered. After learning Willy was still alive, though, nobody seemed worried: “He’s got it good, now. Two or three weeks in the hospital, with clean sheets, a real roof over his head, new clothes, free food, nurses … I want to go there, too! Only there’s no wine. Poor Willy!”

My salary, at day’s end, was a small pouch of Bull Durham tobacco, rolling papers, two dollars, and the bedroll for Pete, consisting of a green blanket, comforter, and a length of twine.

Back at the jungle, BB and Pete were packed and ready to continue west, this time to Wenatchee, in central Washington. Pete grunted his thanks for the bedroll and then sat silently. After rekindling the fire, I reached for my knapsack to get out a can of chill I knew I had there. But … one of two straps on the knapsack had been left undone, and not by me. Odd. Maybe Pete or BB had needed some little cooking item, I thought, and had taken a quick look to see if I had it. It was a violation of etiquette—you never went in another tramp’s pack without permission—but probably not serious.

Yet the chill was not where I had put it. And where were the old cotton gloves I used as hot pads when cooking? And my knit hat that was gone, too. Suddenly I became alarmed. I looked over toward the campfire BB was sitting there, chewing on a match and staring into the flames and Pete was gone. My railroad maps the maps I had not told them about, which had been so hard for me to find, had been hidden at the bottom of the pack. Now they were gone, too. Apprehension grew in my stomach. To mention this or not to …

“Hey, uh, BB,” I said, deciding. “Were both you and Pete around all day?”

“Well, yeah, I believe we were,” said BB, closing the only route of escape from the impending conflict.

“That’s funny. Stuff is missing from my pack.”

“Oh, yeah? Like what?”

I recited the list, including the train maps.

“I didn’t know you had no train maps.”

“Well, I did.”

BB chewed silently on the match, not looking at me. “So, you want to search my pack, right?”

“No, I don’t want to, but I don’t know any other way to go about this.” The offer had caught me off guard.

“Well, there it is. Go ahead. I got nothin’ to hide.” He gestured toward his small carry bag. I looked at his bedroll, too, to which he had tied Brandy Lee. If he had offered to let me search his little bag, the stuff was probably in his bedroll.

“Okay if I look at your bedroll after that?”

“Sure.”

I approached his pack, on the ground next to BB, my anger growing. I knew I had to ask this of them if I didn’t press it, what would be taken next? How far behind the loss of respect for my property would be the loss of respect for my person? Yet, as I reached into BB’s bag, I was scared. BB, clench fisted, hovered above.

“Careful my knife’s in there,” said BB. It was an oblique threat.

My missing gear was not in the bag. I stood up. BB straightened, too, raising himself to his full height, a head above me. I gestured toward the bedroll.

“What should I do with Brandy Lee?” I asked.

“You’ll leave her right fuckin’ where she is, you son of a bitch!” snarled BB.

I stepped back. “You said I could look in your bedroll.”

“Sure, you can look in it,” he said, “but if you don’t find your map I’m gonna bash your motherfuckin’ head in.”

It was just like with Roger. Everything fine one second, and then the next bam. Complete changeover. But I was not drunk, and I had a dispute to resolve with BB.

BB advanced. I took another couple of steps backwards, out of the range of his fists, and put my hand in my pocket. “I don’t want no trouble, BB just my stuff back.”

He wasn’t even listening. BB, prison trained, was sizing up the fight. He stopped walking toward me.

“I see you got your piece,” he said, eyes on my pocket. “Well, I got mine, too.”

He thought I had a gun, a mistake that would work in my favor. He claimed to have a gun, but I was almost certain he did not: few tramps did, because of a gun’s high pawn value. Also, BB almost certainly would have told me about it before, in his own menacing way, if he did have it. But things were moving too fast. All I knew was that BB had stopped moving toward me. And his knife, in the pack, was closer to me than to him.

“Look, man, all I want is for us to be fair and square with each other. You don’t want your ass whipped by me, and I don’t want mine whipped by you. So play it straight with me.”

“I tell you what, if I didn’t have no faith in the sumbitches I was travelin’ with, I wouldn’t be travelin’ with the motherfuckers,” said BB, drawling at triple speed. “And if I lost somethin’, I wouldn’t go lookin’ through your shit, I’d say, ‘Yeah, I take your word for it, man,’ and all that. And then I’d just go lookin’ for the shit.”

“If I didn’t find it,” I returned, “I’d owe you an apology, and I’d give it.”

“I don’t accept fuckin’ apologies, I sure as fuck don’t,” said BB heatedly. “They ain’t worth the fuckin’ paper it’s wrote on.”

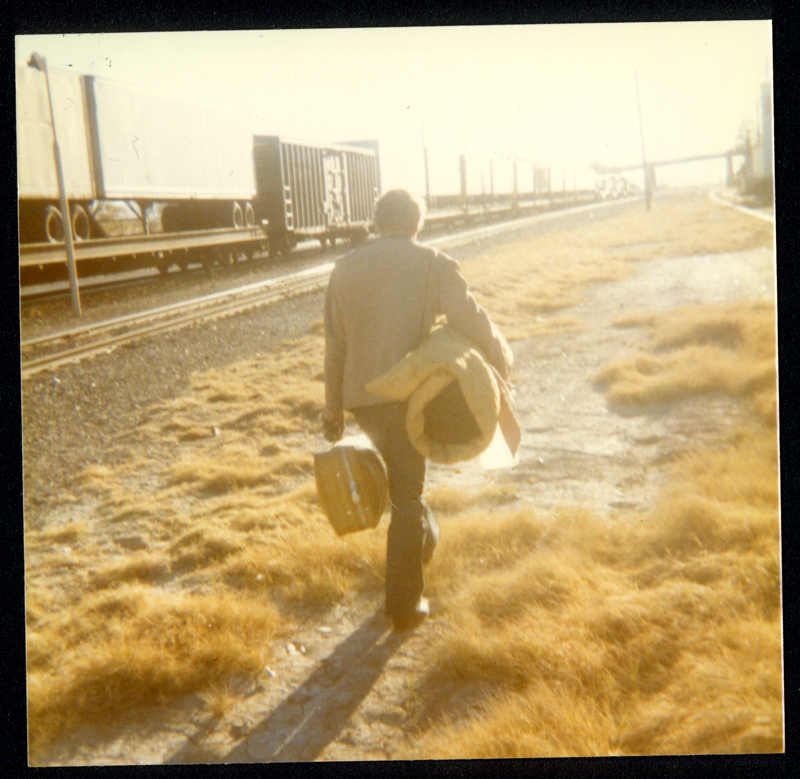

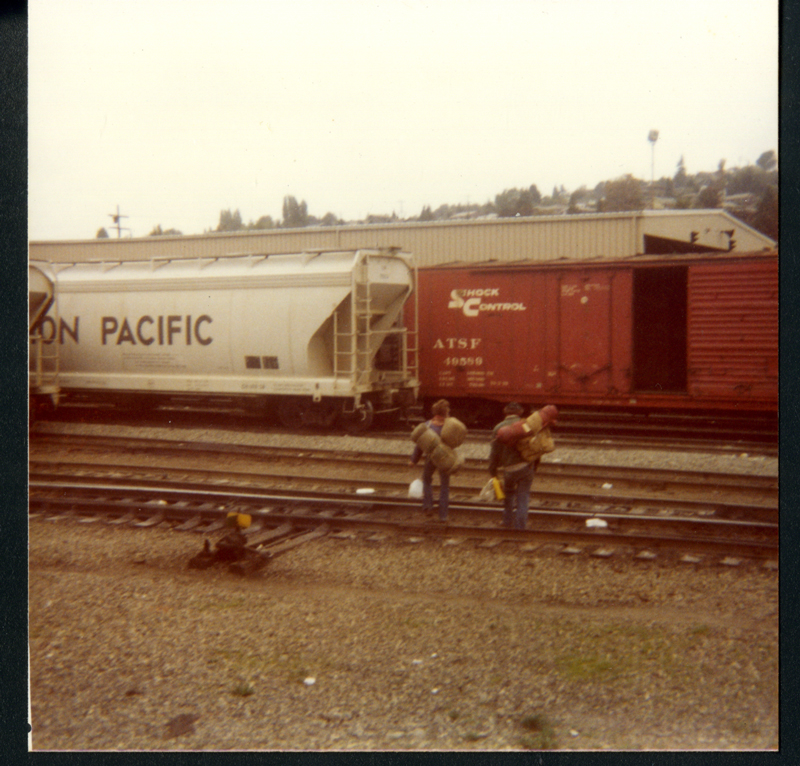

Pete, I noticed, had quietly returned to pick up his gear, and was starting to leave. BB, still hollering, started to do the same. Along with his own bedroll, he picked up the one I’d gotten for Pete. I moved suddenly toward him as he did, my only offensive move of the night.

“You’ll leave that,” I said.

He drew back from the blankets, cursing me. He and Pete, with Brandy Lee trailing, began crossing the yard toward the tracks.

Pete’s neutrality infuriated me. “Hey, Pete,” I cried after him. “What ever happened to ‘all for one and one for all’? Here we are, friends one minute and the next you split without a word. What happened, did you lose your voice?”

“You shut the fuck up, man,” said BB, turning around and shaking a fist at me. “You ain’t been straight with us.”

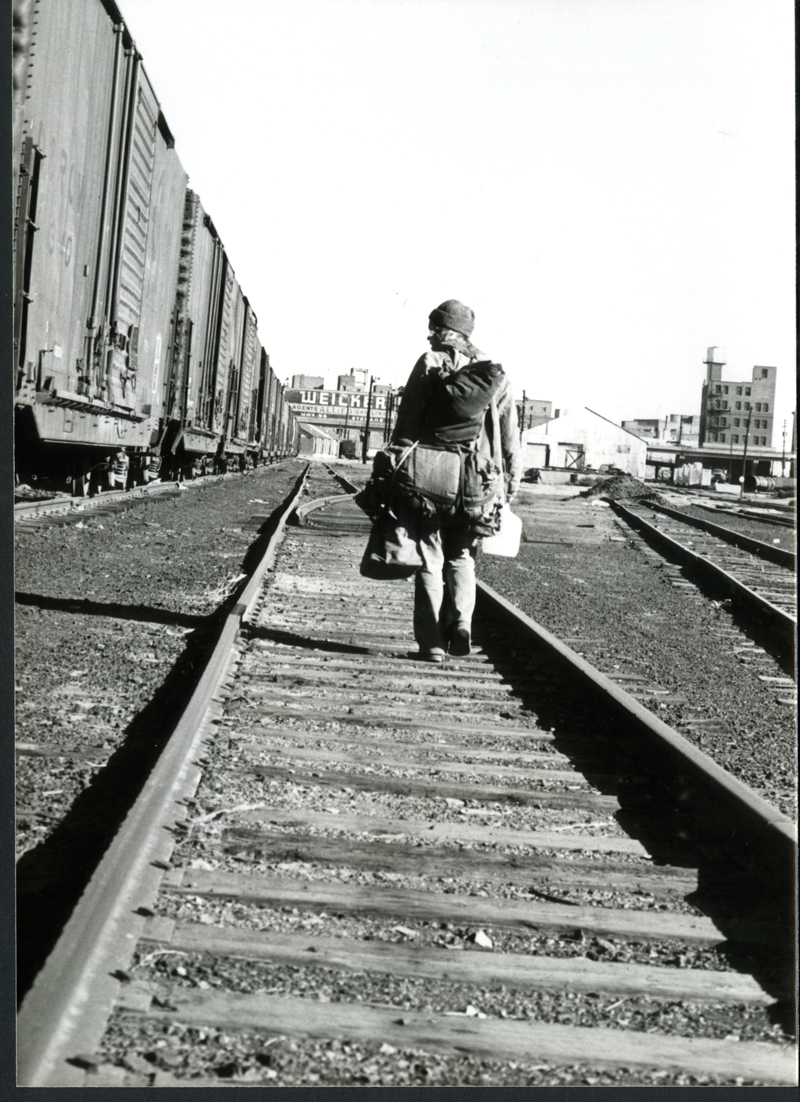

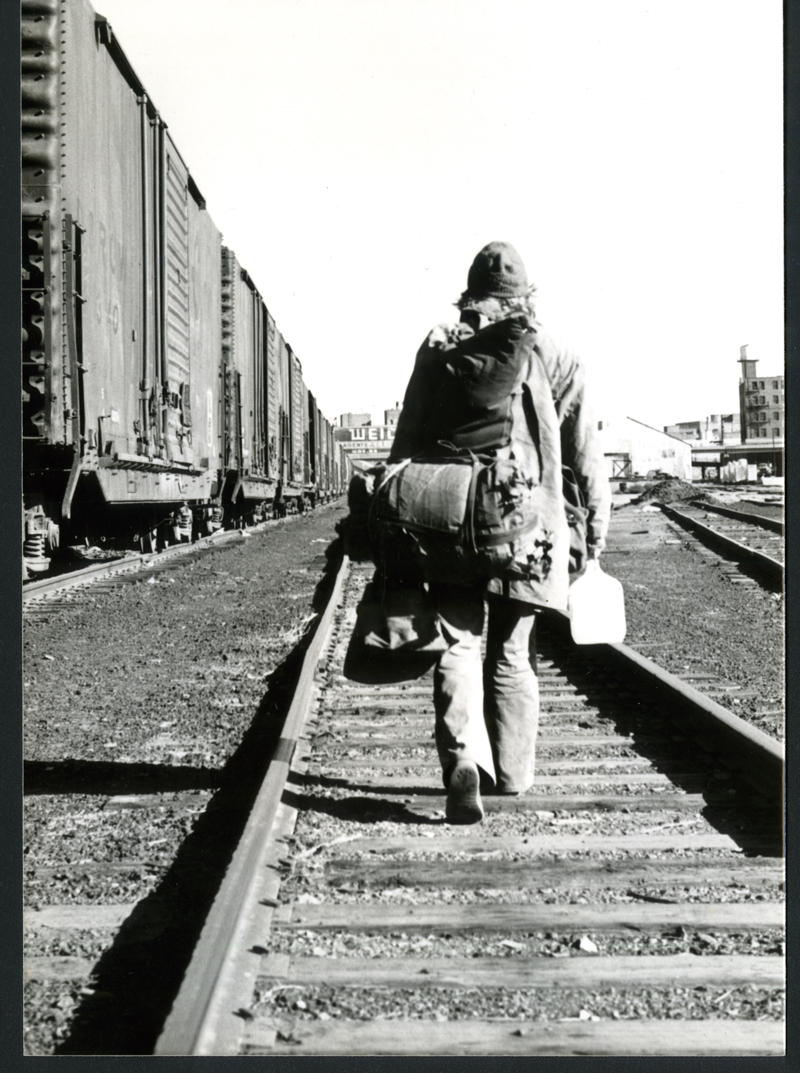

“What the hell do you mean by that?” I said. But they disappeared into the strings of trains. I stood alone in the field, desolated and stunned. More than two weeks of round the clock companionship had just unraveled in about three minutes.

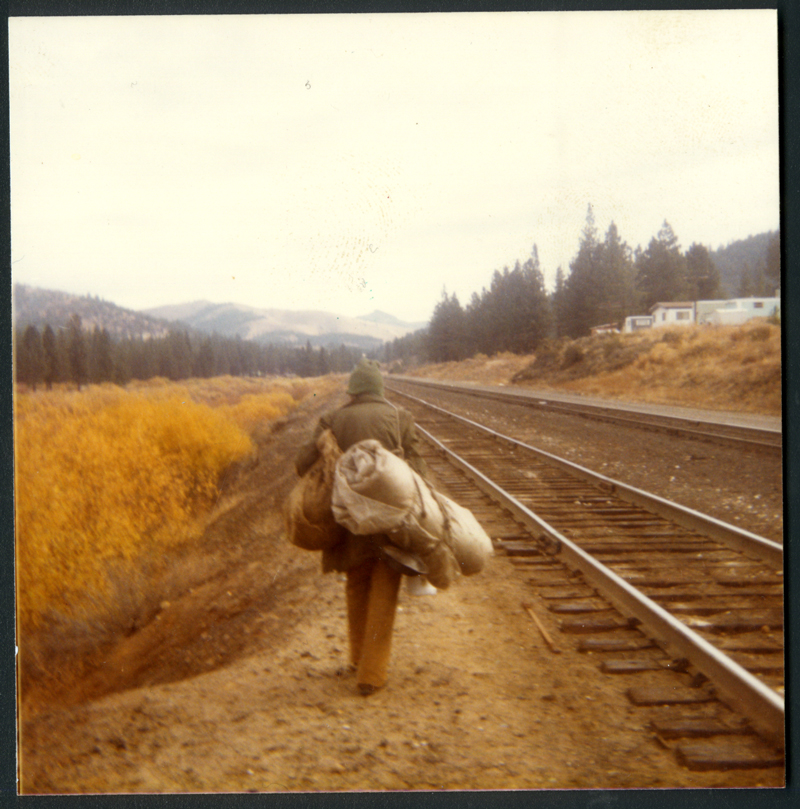

Gradually my heart slowed, and replacing the anger and adrenaline was fear. The field seemed suffused with BB’s malice. I was afraid that he might circle around, trying to catch me unawares while I slept. I couldn’t bring myself to eat anything at all. I repacked my gear and walked away, disposing of Pete’s bedroll in a ditch as I headed toward the main road. I didn’t want any tramp to have it.

To my disgust, two tramps walking in the opposite direction approached me to ask about the jungle conditions. I answered curtly, but they kept talking, filling me in on life at the Spokane rescue mission, though I hadn’t asked. Slowly, I began to listen; it sounded like a good destination. Then, to my surprise, I told them why I was leaving the jungle. They seemed genuinely sympathetic. “Town’s about five miles from here,” said one. “You oughta take the bus. Got change?”

I did not.

“Here,” he said, and handed me a quarter, dime, and nickel. “That’s handicapped fare, so just make sure you look it. And if that mission’s full, you just come back and jungle up with us, okay?”

“Okay,” I said. The moment I turned, my eyes flooded with tears. I waved them good bye without looking.