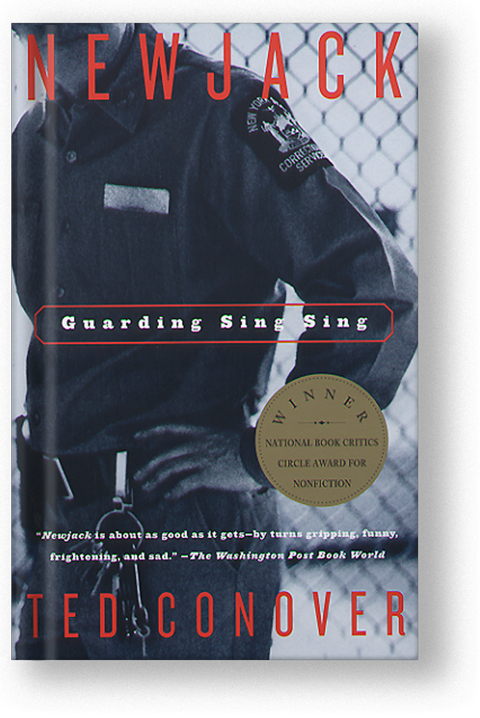

Newjack

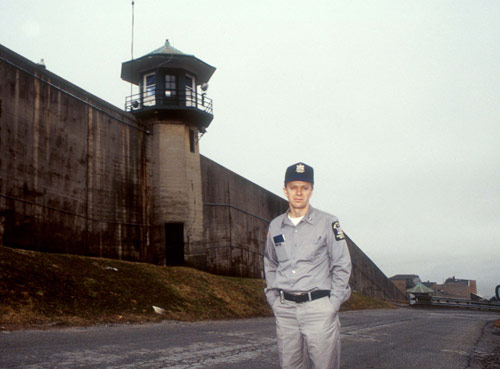

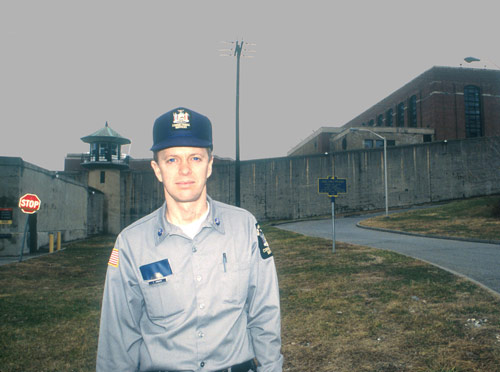

Guarding Sing-Sing

Book

From the book jacket:

Ted Conover, the intrepid author of Coyotes, about the world of undocumented Mexican immigrants, spent a year as a prison guard at Sing Sing. Newjack, his account of that experience, is a milestone in American journalism: a book that casts new and unexpected light on this nation’s prison crisis and sets a new standard for courageous, in-depth reporting.

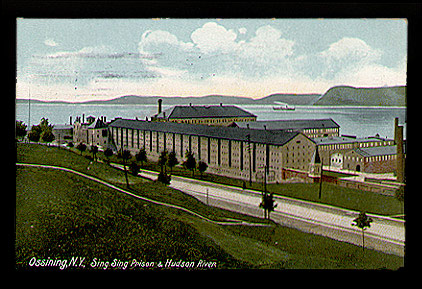

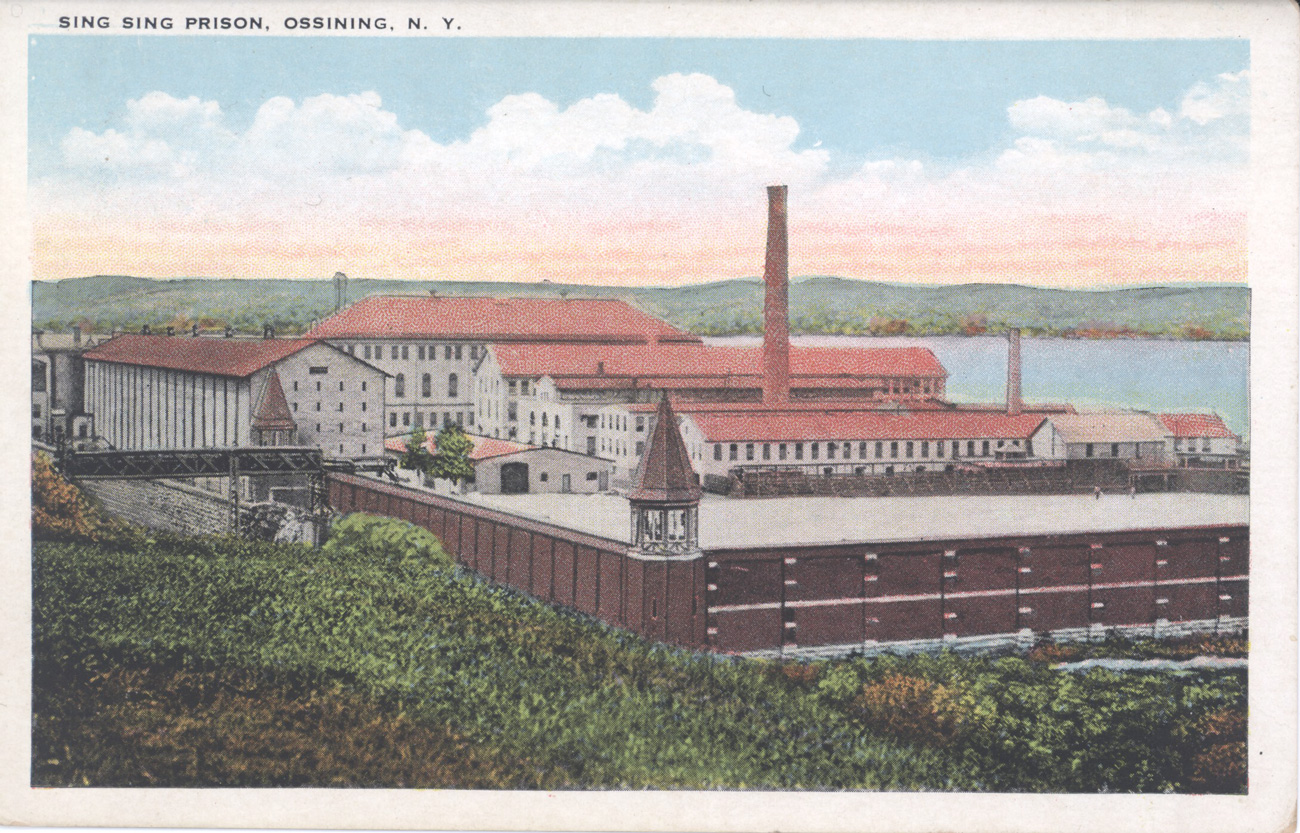

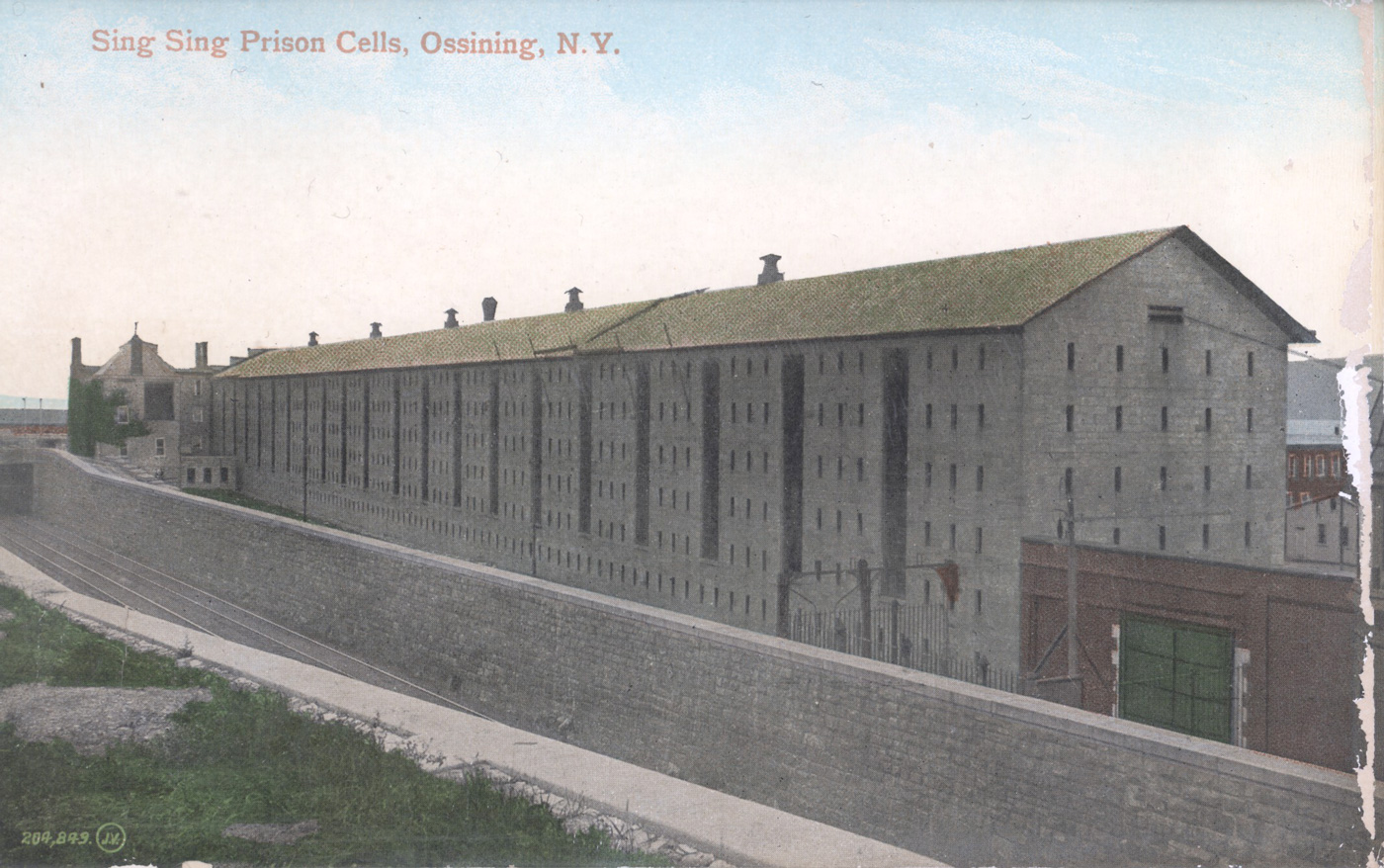

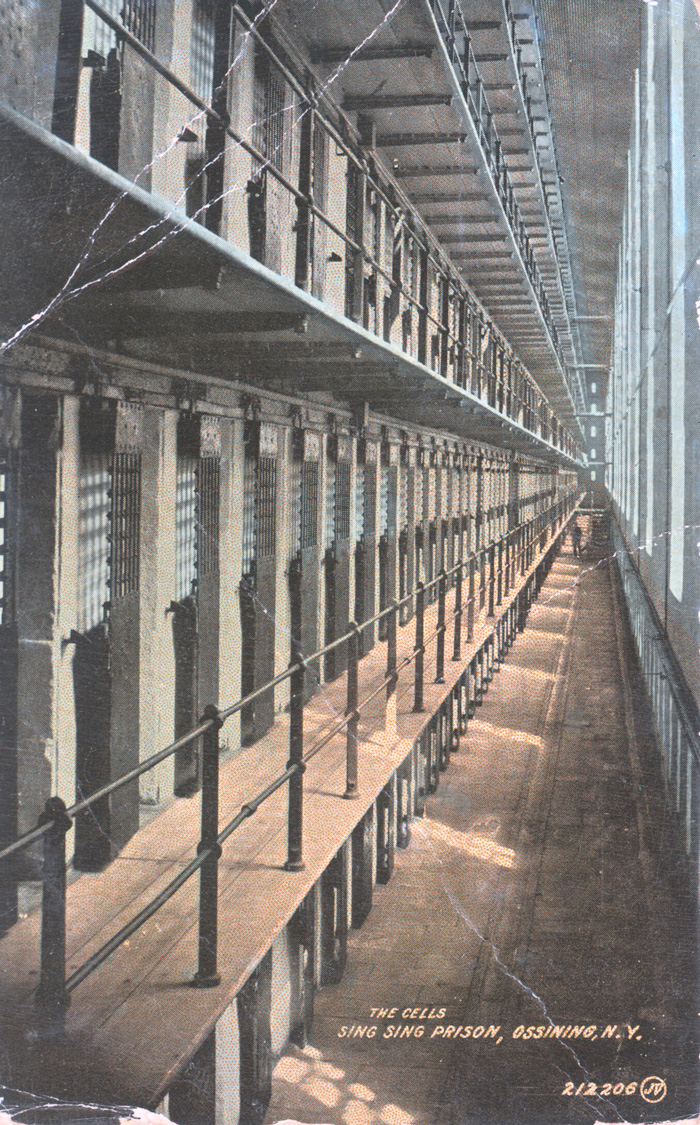

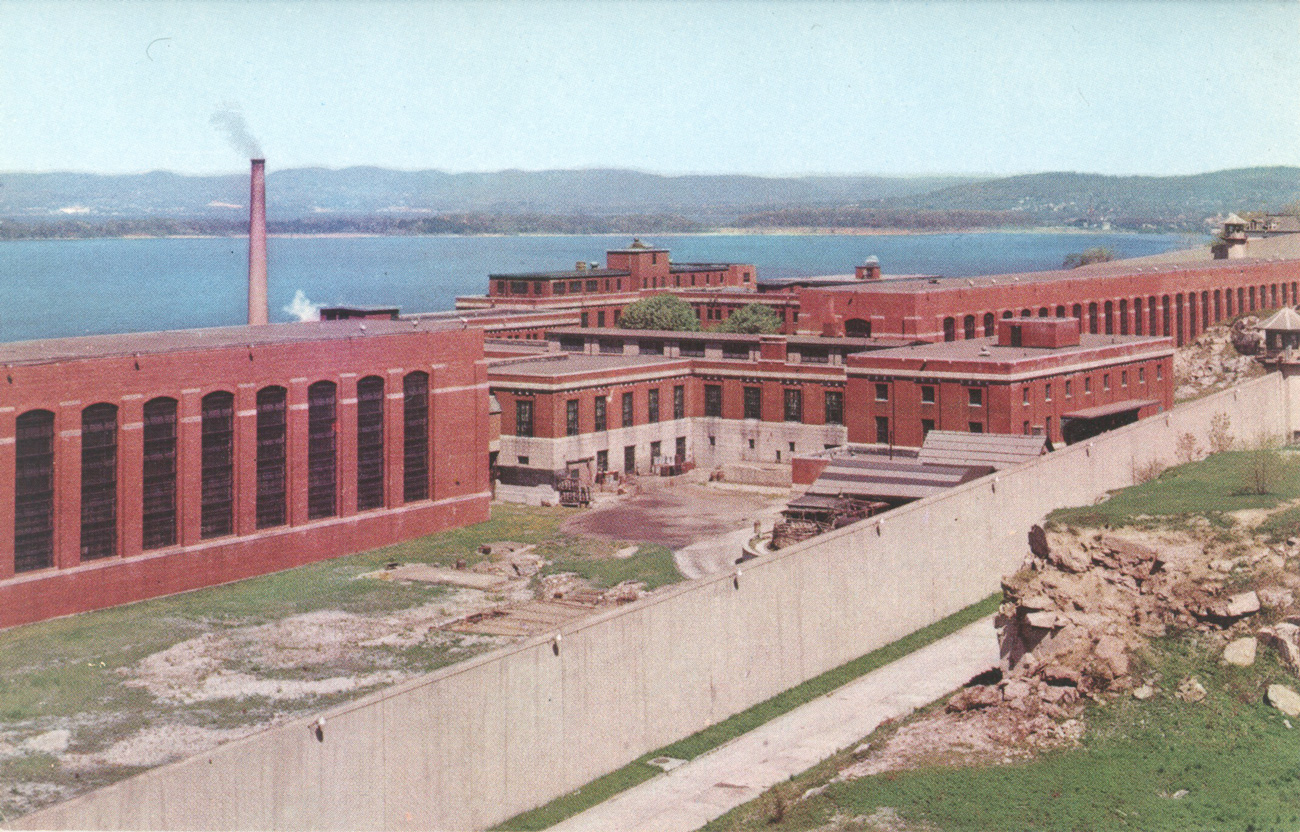

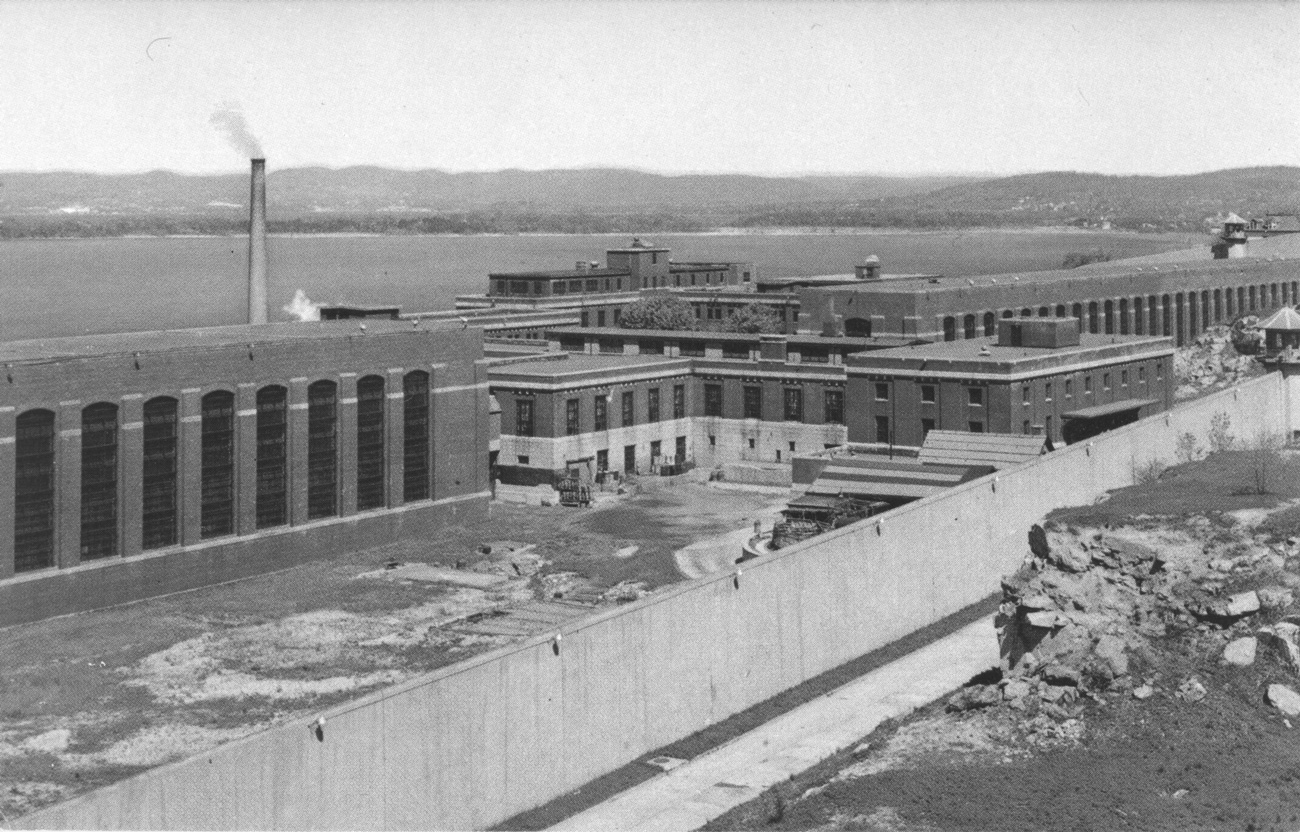

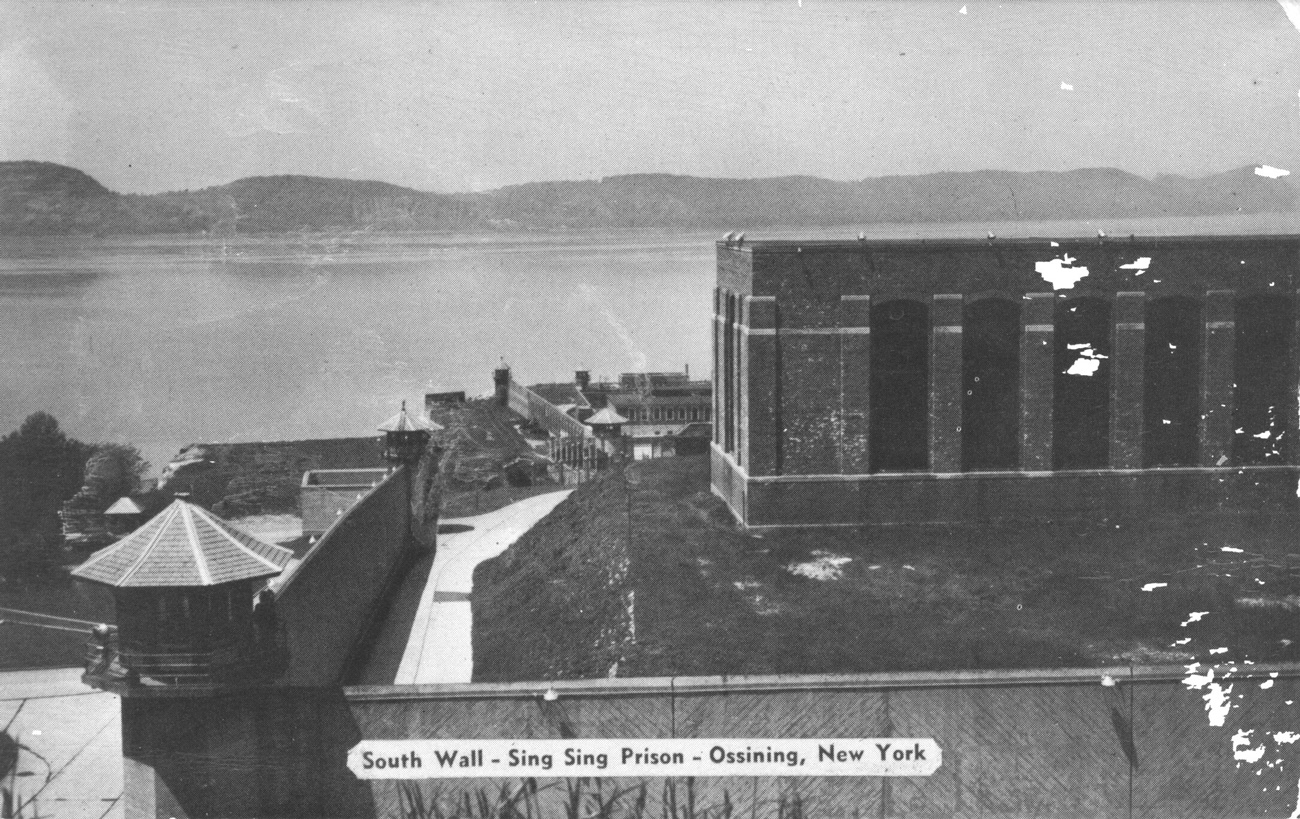

At the infamous Sing Sing, once a model prison but now New York State’s most troubled maximum-security facility, Conover goes to work as a gallery officer, working shifts in which he alone must supervise scores of violent inner-city felons. He soon learns the impossibility of doing his job by the book. What should he do when he feels the hair-raising tingle that tells him a fight is about to break out? When he loses a key in a tussle? When a prisoner punches him in the head? Little by little, he learns to walk the fine line between leniency and tyranny that distinguishes a good guard.

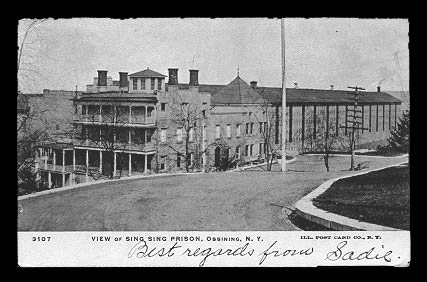

Along the way, we meet a cast of characters that includes a tough but appealing supervisor named Mama Cradle; a range of mentally ill prisoners, or “bugs”; some of the jail’s more flamboyant transvestites; and a philosophical, charismatic inmate who points out to Conover that the United States is building new prisons for future felons who are now only four and five years old. Conover also gives us a history of Sing Sing (it was built by inmates, and for decades was the nation’s capital of capital punishment) in a chapter that serves as a brilliant short course in America’s penal system.

With empathy and insight, Newjack tells the story of a harsh, hidden world and dramatizes the conflict between the necessity to isolate criminals and the dehumanization–of guards as well as inmates–that almost inevitably takes place behind bars.

Reviews

Winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award

Pulitzer Prize Finalist

Entertainment Weekly’s Best Nonfiction Book of the Year

One of USA Today’s Ten Best Books of 2000

New York Times Notable Book

Chicago Tribune Critics Choice

Library Journal Best Books of 2000

“An amazing book about life in prison. … ‘Newjack’ is about as good as it gets-by turns gripping, funny, frightening and sad. … The stories are spellbinding and the telling is clear and cold. But Conover doesn’t just want to chill us or gross us out. He wants us to think about prisons and to rethink them.”

– The Washington Post

“George Orwell, you have a godson. Upton Sinclair, you’ve been one-upped. … In this mind-blowing example of journalism at its most authentic, Conover discovers that prison can bring out the animal in any man, and even the zookeeper has to protect his soul.”

– Entertainment Weekly

“Newjack is an astonishing work by a gifted and dedicated journalist. Ted Conover takes us into the dangerous, sad, amusing and instructive soul of one of America’s best-known prisons.”

– Tom Brokaw

“[H]is straightforward sentences have accomplished something formidable; he has made us fully part of his experience. … [C]ompelling and inescapable…. [I]t is hard to imagine any journalist doing his more daringly or effectively. … ‘Newjack’ coheres as a moving indictment of our ways of punishment.”

– The New York Times Book Review

“Nobody goes to greater lengths to get a story than Ted Conover. Immersing himself in his subject to a degree matched by few journalists working today, he has given us a compelling, compassionate look at a terribly important, poorly understood aspect of American society. My hat is off to him.”

– John Krakauer

Excerpt

From Chapter 6, “Life in Mama’s House”:

“Take your shirt off, please. Show me your hands, both sides. Now, arms away from your body. Turn around. Okay.”

A nod when we’re finished, and we move on to the next cell. He’s heard us coming and wants to know why.

“You can probably guess. just do it, please.”

“And what if I don’t?”

“The sergeant will come, and they’ll write you up.” The man sighs, shrugs, pulls his T shirt over his head, does the dance. We move on to the next cell.

B block is locked down, and we’re looking for knife cuts. it is May. For the third day in a row, the Latin Kings have been attacking the Bloods, and vice versa. Not en masse just stealth encounters, stabbings without warning. One incident provokes the next; we’re told that the cycles of retaliation began at Rikers Island earlier this month. Each time we let the inmates back out, someone else is attacked, violence flaring up like one of those trick birthday candles.

The sergeant wouldn’t say why we were conducting these “upper body frisks,” but it doesn’t take a genius: The white shirts think that at least one participant in the latest cutting exchange, though wounded, escaped undetected. So we’re looking for blood, skin that needs stitching, a gash from a homemade blade.

At the next cell, the inmate is lying on his bunk. “R 63, take off your shirt, please.” He sits up bleary eyed, then stands, removes the shirt. Like many inmates, he’s in excellent shape from weight lifting. And like many inmates, he has scars: three inches long on his waist below the ribs, about one inch long on his arm, penny size circles that look like two bullet wounds on a shoulder blade.

“Nothing fresh,” says the officer I’m with, more to himself than in dismissal. He’s an old timer who doubts we’ll find anything and acts like he’s seen it all before. I’m not so world weary. The huge number of scars surprises me. Half the inmates seem to have been stabbed or shot at some point in their lives. Often, the scars are on their face: a pale, thick line across the back of the skull where no hair grows, a sliced nostril imperfectly healed, a gash along a cheek that ended when the blade passed through a lip. The most ghastly wound is on a man who looks about nineteen: a ragged cicatrix that winds from one corner of his mouth to beneath his left ear, then all the way around his head, under the right ear, and back to the other corner of the mouth, as though the assailant intended to peel off the top: a sadist’s trophy.

We continue down the line. Gash after gash after gash. But nothing fresh.

From Chapter 7, “My Heart Inside Out”:

Some officers fed on the violence, I knew. Phelan and Pacheco were probably two of them. Pacheco had been talking the day before about how many new uniforms he’d had to buy because of all the blood he got on them. He’d made it sound like a complaint, but I knew it really wasn’t. A new uniform was a CO’s Purple Heart.

We rounded the last corner, nodded at the officer at the gym door, and headed toward the front gate and freedom. But there was music an inmate was playing a tape loudly from his cell. This was forbidden: Inmates had to use headphones. “Turn that down,” said Phelan, the biggest of us.

The inmate only pretended to turn it down. “Hey,” said Phelan, and we all stopped.

The inmate looked up at Phelan defiantly. “The gallery officer don’t care. What’s it to you?” he demanded. “You’re just talking big ’cause you’re on the other side of those bars.”

The gallery officer was standing just a few cells down. Phelan grabbed the keys from the guy’s belt, strode over to the inmate’s cell door, unlocked it, and flung it open with a bang. He reached over, yanked the tape player out of its plug, and stood in the doorway holding it like a club.

“Now I’m not,” he said fiercely. “You want to come out?”

I had never seen an inmate cower so, and for good reason Phelan’s stance said he was ready to take the man’s head off. The show was gratifying to watch; Phelan was not afraid to put his massive physical presence to work. The little touch of Elam Lynds was good for our morale.

Violence and the potential for violence were a stress on inmates and officers, but not on all of them, and not all the time. There were moments when, due to the constant tension of prison life and the general lack of catharsis, violence and the potential for violence became a thrill. It had been a long, hot summer in B block–a long, low wave of attacks and reprisals, and then lockdowns to let everything cool off. Following almost every series of incidents, officers would search the yard, the gym, and other places inmates congregated and prepared for battle, looking for weapons. Usually, we would find scores of them in trash cans, under rocks, on ledges, or just beneath the dirt. Sometimes our efforts seemed to forestall the next wave, sometimes not.

I remembered the day I’d been standing outside the commissary, waiting to escort my inmates back to B block, when the gate officer told me there’d be a delay some kind of fight had broken out in the block. Frustrated that I’d missed it, I paced the floor, locked my inmates behind another gate, and waited for some news. Then, up the tunnel from B block, a long succession of officers and handcuffed inmates came into view. The first three inmates were bleeding badly around the head; the officers wore latex gloves. The inmates I was in charge of shouted out encouragement and support.

“Did you get the motherfucker?”

“Yo, Smiley!”

“Ernest, my man!”

The handcuffed, injured inmates looked not despondent but electrified. Regardless of their wounds, they looked utterly thrilled by what had just happened.

Finally we got to return to the block, which by now was locked down. I helped make sure my group of escorted inmates got locked into their cells, then went down to the flats. My friend Scarff was working Movement and Control, next to the OIC’s office. A group of us asked him to tell us what had happened.

Apparently, three or four inmates had chased and beaten two others as they were leaving the gym. The pursued inmates headed toward the OIC’s office, where officers were congregated. When the officers realized what was happening, several of them, including Scarff, chased the attackers back down toward the gym. There had been pileups of officers and inmates; Scarff had recovered a shank. One of the assailants, as his victim was marched by in handcuffs, his shirt bloodied, had gleefully taunted him, “I got you! I got you!”

Scarff wasn’t a newbie like many of us others; he had worked corrections in Maryland before coming here. But he now seemed as excited as the inmates had been.

“It was the first time in five years that I’ve been involved in a major incident,” he said. “And I loved it! I wanted to hit somebody!” It seemed that Scarff had experienced some of the same intoxicating rush that the inmates had felt. It made all kinds of sense. There were so many unresolved angry exchanges in Sing Sing, so much that never got settled. How many times had I heard an inmate or an officer say, semi-facetiously, “I’m gonna set it off!” Light a fuse! Start a little chaos! In some warped and exaggerated form, it seemed like the same kind of impulse as getting wild on a Saturday night, letting off steam after a week of tension or boredom.