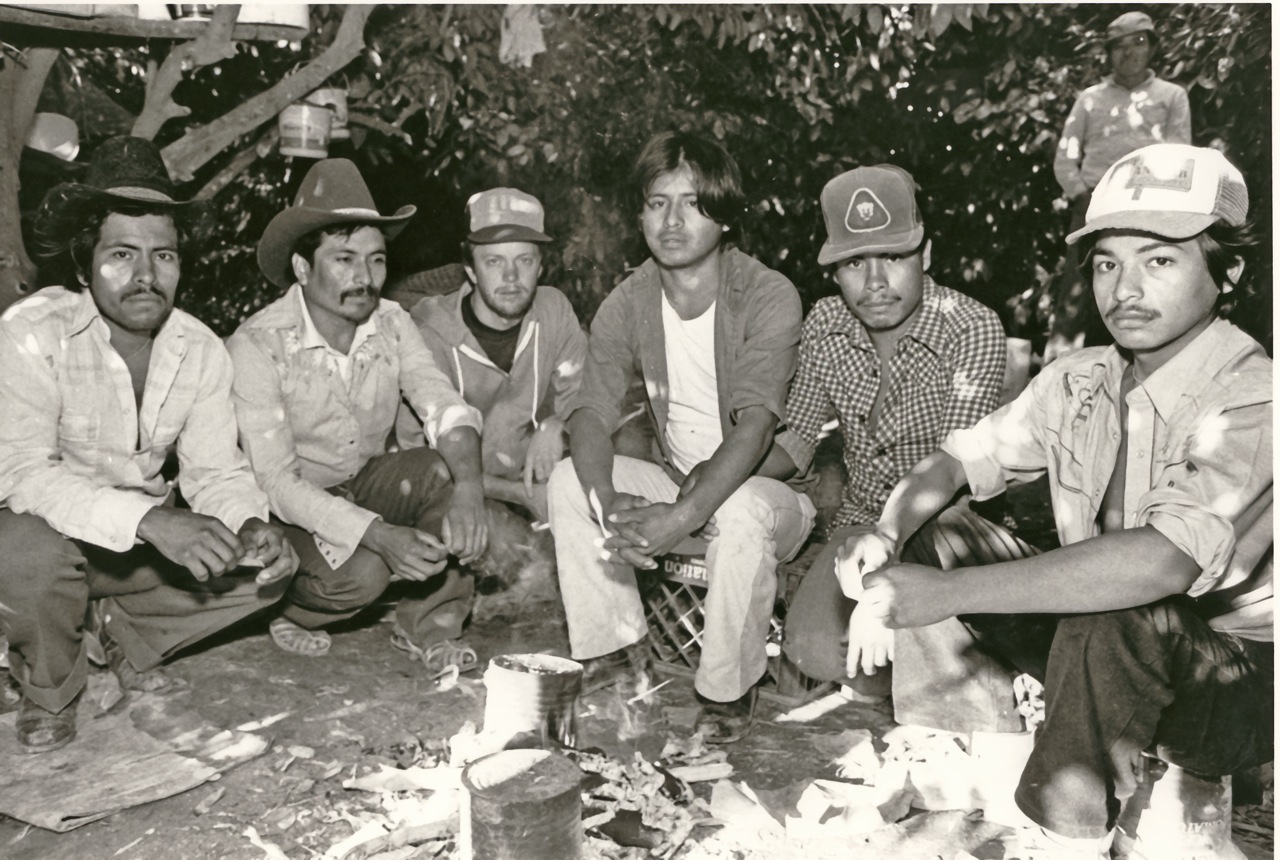

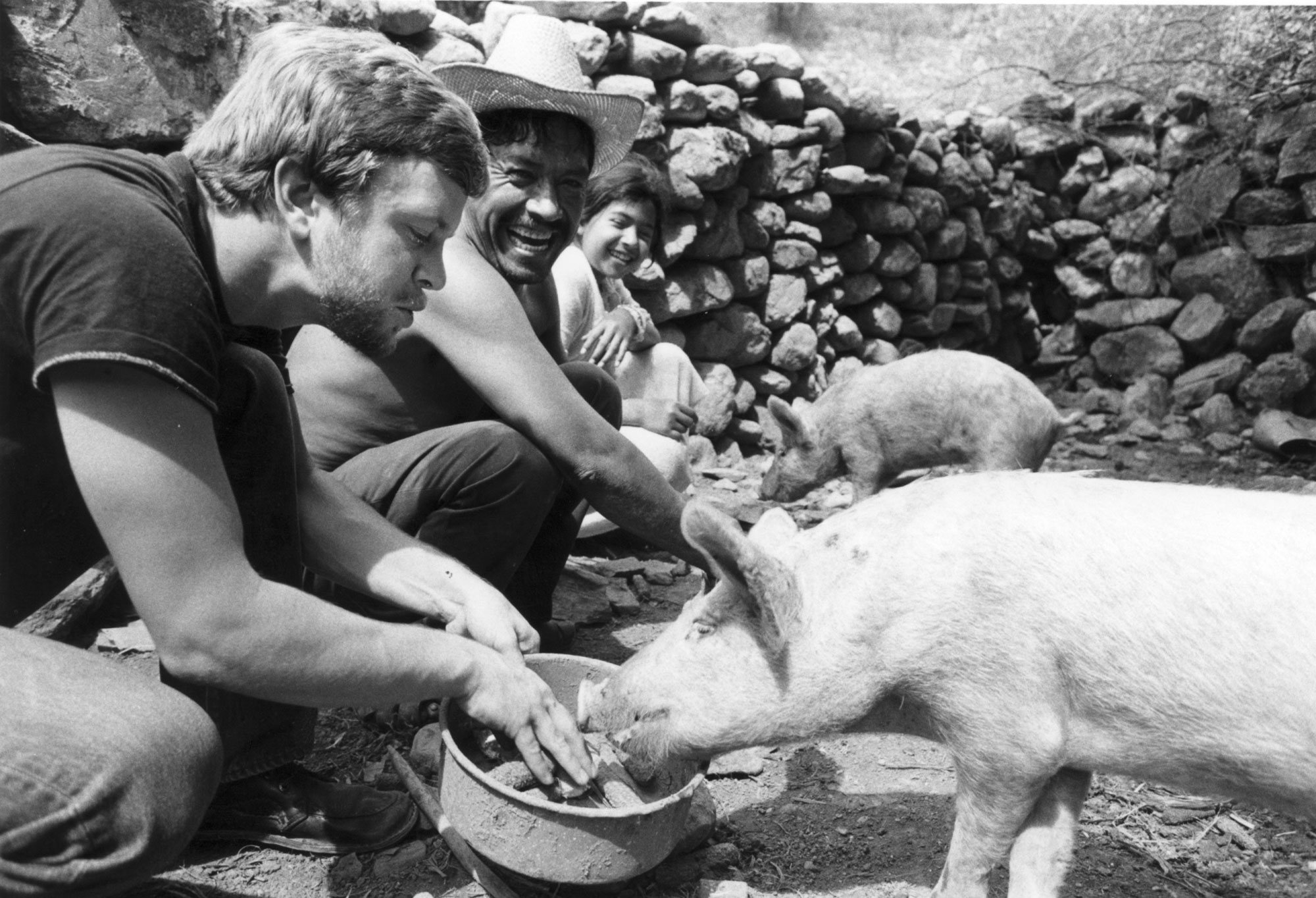

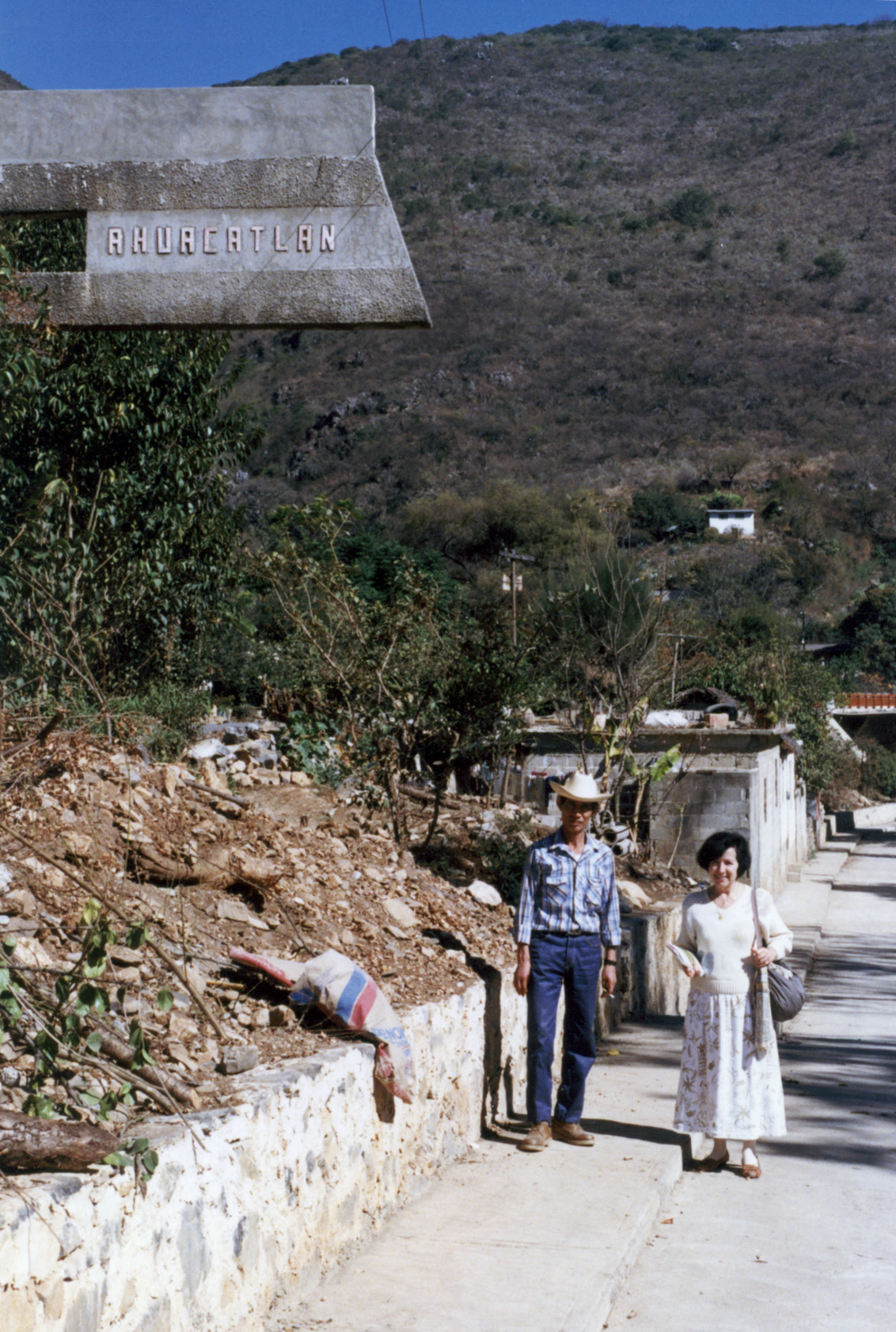

The next weekend I was called in as a substitute during the last fifteen minutes of the Tecos’ game. A fortnight later the same thing happened, and a week after that, I got a spot on their relay team for the province’s annual “Marathon of the Mountains” footrace. Other outings cemented my friendship with Jesús, Tiberio, Conce, and Victor: an afternoon spent drinking the excellent pulque of Doña Rosa, a tough Ahuacatlán widow; flirtatious visits to the office of Elisa and Elena, young social workers sent from Querétaro City to minister to mountain folk two days a week; more nights in Pablo’s cantina; a tour to see the annual milling of sugarcane at Pepe Pacheco’s, where a horse tied to a beam walked endless circles around Pepe’s grinder and dried cane husks fueled a fire that warmed wide evaporation tanks. The rapping of pebbles against the windowpanes of my room was the invitation to another outing, and the days flew by.

Jesús in particular loved to talk about his experiences in the States, usually in the form of anecdotes. Learning English was one of his main preoccupations, and many of the tales concerned the obstacles he’d encountered along the way. One day several of us were seated around the huarachería of Tiberio’s brother Ignacio, watching him and his assistants cut and sew the leather for sandals.

“Teo,” asked Jesús, “how do you say it when a girl is wearing perfume? What do you say to her? ‘I like your smell’? Is that it?”

“I like the way you sm—?”

“Yes, yes, that’s it, ‘I like the way you smell,’ “ he interrupted. “Well, you know what I said to my girlfriend there one night?”

Jesús had dated a number of American girls, none of whom spoke Spanish. I shook my head.

“We were driving in the owner’s car that old Cadillac he gave us and she smelled good, so I took her real close, like this, and I said, ‘Baby, I like the way you stink.’ “

I burst out laughing, and Jesús explained it to the others: in Spanish, you use the same verb for smell or stink, and Jesús hadn’t appreciated the difference. “Did she explain it to you?” I asked.

“Yes, but she was mad!” said Jesús “You know, she taught me some other words too. ‘Be nice,’ she used to say that’s when we were in the car, and, well, you know . . .”

Tiberio made the appropriate body language to describe what they had been up to.

“Ooh, but we made some big mistakes up there. Remember, Tiberio, in the Burger King? They asked if we wanted everything on it. ‘Yes,’ I said, ‘but no mustache.’ ‘What?’ she asked. ‘No mustache,’ I said. I thought I was saying ‘mustard.’ ”

Another time he had suggested to his girlfriend a dinner at the Pussycat—”Pizza Hut” he had meant to say—and yet another time, he had asked the foreman if he could borrow the “fuck you” from his trailer.

“What?” said the foreman.

“The fuck you,” repeated Jesús, a bit nervously—he knew the phrase had a bad meaning, but thought it also meant “vacuum.” The words sounded identical to him. So did “eyes” and “ice.” These confusions had gotten him into lots of trouble, he said, offering extra explanations to the others in the room so they would understand what he was telling me.

One of the most rapt listeners was a middle aged man squeezing rivets into straps of leather for the huaraches. “Ay, English,” he said. “They say it’s the hardest language in the world.”

“No, Chinese is the hardest,” offered Ignacio, also middle aged. As these men debated the point, I realized something extraordinary was happening here: these older Mexicans were listening closely to men barely into their twenties. Age was the traditional determinant of who listened to whom in rural Mexico, older men seldom having time for younger men’s stories (neither group, at least in public, appearing to have time for women’s)–but here, emigration to the States had the town turned around. The young guys were heading out, earning in a week up north what their fathers would toil months for. They returned to constitute a higher class of men, wealthier and more experienced, if less wise. Father Cano was right: in ways both subtle and obvious, emigration was setting Ahuacatlán on its head.

“English is a thousand times harder!” the older man continued, now rather heatedly.

“That’s not so!” countered Ignacio. “Chinese has thousands of letters, and difficult sounds. Who do you know that speaks Chinese?”

The debate was escalating to an absurd degree: Ignacio and the old man had put down their work and were now yelling. The younger guys were murmuring that perhaps I ought to offer an opinion and put a stop to it—but I didn’t want to take sides. Finally Tiberio stood up, interrupting them, and asked if we knew the joke about learning Chinese. Nobody did.

“How long did the Russian say it took to learn Chinese?” he asked the room. There were shrugs. “Five years,” said Tiberio.

“How long did the American say it took?” Again, shrugs. “Four years.”

“Okay, how long did the Mexican say it took?” Sensing that a punch line was imminent, men started smiling. “He said ‘ten years,” offered one. Tiberio shook his head.

“The Mexican said, ‘When’s the test?’”

It was a masterful move; in their laughter the older men forgot the squabble. Jesús nudged me. “That’s the reputation we Mexicans have—everything ‘mañana,’ right?”