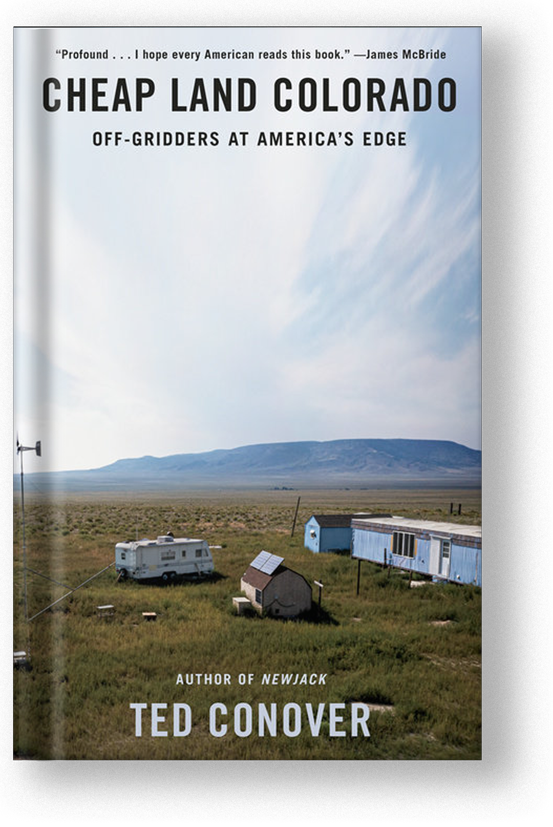

Cheap Land Colorado

Off-Gridders at America's Edge

Book

Reviews

“BEST BOOKS OF 2022” – THE NEW YORKER

_

“50 NOTABLE WORKS OF NONFICTION 2022” – THE WASHINGTON POST

“One of our great narrative journalists . . . Conover’s approach isn’t so much about pinning people down as letting them reveal themselves. He’s such a wry and nimble writer that much of the time this works, yielding rounded portraits that are full of ambiguity, anguish and contradiction.”

– Jennifer Szalai

“Engrossing . . . Nothing motivates the journalist Ted Conover like a no-trespassing sign. . . . One of Conover’s strengths as a writer is that he is willing to let his subjects ‘say their piece.’ He is wonderfully open to people’s understanding of themselves, even when he sees the world very differently. . . . With his thorough and compassionate reportage, Conover conjures a vivid, mysterious subculture populated by men and women with riveting stories to tell. To read Cheap Land Colorado is to take a drive through a disquieting, beguiling landscape with an openhearted guide, windows down, snacks in the cooler, no GPS. It’s a ride I didn’t want to end.”

– Jennifer Reese

“Consistently interesting to read . . . Full of remarkable characters . . . Conover has a good eye for the particularity of life on the flats.”

– The New Yorker

“Over the years, Conover has mastered the difficult balance that first-person reportage requires; he is a character in the story — an observer, participant and narrator — but the story is not about him. . . . The strength of this book lies in Conover’s voice, confident, observant, nonjudgmental.”

– Laurie Hertzel

“What sets Conover’s work apart is its engagement and its rigor, the care with which he embeds himself. Cheap Land Colorado is a case in point, a book that gains as it grows.”

– David Ulin

Excerpt

Prologue

It begins with a moment of contact—of driving up to a homestead and trying to introduce yourself.

The prospect is daunting: a lot of people live out here because they do not want to run into other people. They like the solitude. And it is daunting because many of them indicate this preference by closing their driveway with a gate, or by chaining a dog next to their front door, or by posting a sign with a rifle-scope motif that says, “IF YOU CAN READ THIS YOU’RE WITHIN RANGE!”

The local expert on cold-calling is Matt Little, charged by the social service group La Puente with “rural outreach.” Matt has let me ride around in his pickup with him so that I can see him in action. Distances between households on the open Colorado prairie are great, which gives him time to explain his approach, which he has thought about a lot, as he does this every day and in three months has not gotten shot.

If you’re thinking the checklist is short, you’re mistaken. Before you ever see the homestead, you need to consider the visual impression you’ll make. Matt drives a 2009 Ford Ranger with a magnetic “LA PUENTE ” sign on the door. It is not fancy. Nor is Matt fancy: he is a forty-nine-year-old veteran of two tours in Iraq, a slightly built man from rural West Virginia with an easy smile. He smokes cigarettes and often he is whiskery. He tells me not to wear a blue shirt, because that’s the color worn by Costilla County code enforcement, and you don’t want to be mistaken for them. La Puente ordered him a hoodie and a polo shirt in maroon with their insignia, and he usually wears one or the other, along with jeans and boots.

He’ll drive by a place, often more than once, before actually stopping, so that he can reconnoiter. Is there an American flag flying? That often suggests a firearm inside. Are there children’s toys? Is there a small greenhouse or area hidden behind a fence that suggests that marijuana is being grown? (Initially I thought that might be a good sign, since cannabis can make people mellow. But Matt emphatically said no. “A full-grown plant could be worth a thousand dollars, and people steal ’em!”) More to the point, is anyone even living there? Are there fresh tire tracks? Smoke coming from the chimney? Many prairie settlements have been abandoned or are lived in only during the summer.

Matt had noticed one property with berms constructed inside its perimeter of barbed-wire fence. He saw bullet casings and suspected the owner was a vet with some psychological issues: “I thought he was probably playing war games, reenacting things he’d been through.” He drove by to show me—the place was at the end of a dead-end road, which made it kind of hard to pretend you were just passing by. Matt said that the first few times, he paused at the road’s end, waved at whoever inside might be watching him, and turned around. He continued in that vein over the next month, waving or honking but not lingering, until one day he saw a man outside the house dressed in camo gear. Matt parked his truck and stepped outside.

“I’m Matt from La Puente,” he said. “I’ve got a little wood.” He gestured at the firewood stacked in the bed of his truck, something useful conceived of by his employer as a calling card, an icebreaker.

The man picked up an AK-47. “You’re a persistent son of a bitch,” he said. Then: “How much is it?”

“It’s free,” said Matt.

The guy walked toward the gate. He opened it. He waved Matt in.

Extras

Harper’s Magazine Article

The Last Frontier, Homesteaders on the margins of America

The San Luis Valley in southern Colorado still looks much as it did one hundred, or even two hundred, years ago. Blanca Peak, at 14,345 feet the fourth-highest summit in the Rockies, overlooks a vast openness. Blanca, named for the snow that covers its summit most of the year, is visible from almost everywhere in the valley and is considered sacred by the Navajo.