November 18, 2012

A Snitch’s Dilemma

Kathryn Johnston was doing pretty well until the night the police showed up. Ever since her sister died, Johnston, 92, had lived alone in a rough part of Atlanta called the Bluff. A niece checked in often. One of the gifts she left was a pistol, so that her aunt might protect herself.

The modest house had burglar bars on the windows and doors; there had been break-ins nearby.

Eight officers approached the house, and they didn’t knock. The warrant police obtained, on the basis of a false affidavit, declared they didn’t have to – the house where their informant had bought crack that day, the affidavit said, had surveillance cameras, and those inside could be armed. Because they couldn’t kick down the security gate, two officers set upon it with a pry bar and a battering ram in the dark around 7 p.m. on Nov. 21, 2006.

Burglars, Johnston probably thought, or worse – an elderly neighbor had recently been raped. No doubt she was terrified. That is why, as the cops got closer and closer, she found her gun. And why, as the door was opening, she fired one shot. It didn’t hit anyone. But it provoked a hail of return fire – 39 shots, 5 or 6 of which hit her (and some of which struck other policemen). By the time the officers burst inside, Kathryn Johnston lay in a pool of blood.

Waiting outside, in the back of a police van, was the small-time dealer who told the police there were drugs in the house. He did so under pressure: earlier in the day, three members of the narcotics team, working on their monthly quota of busts, rousted him from his spot in front of a store. Tell us where we can find some weight, they said, or you’re going to jail. The dealer climbed into a car with them and, a few blocks away, to save his own skin, pointed out Kathryn Johnston’s house – it stood out from the others on the block because it had a wheelchair ramp in front.

How did the dealer feel as he watched the home invasion, heard the fusillade of shots? And, inside the house, how long did it take for the police to realize their grave error and for some of them to decide to handcuff a fatally wounded woman and plant drugs in order to cover it up?

Alex White was at his mother’s house several miles away that evening. She called him downstairs when she heard the news on TV, using a nickname from his childhood (it was the way he first pronounced his own name): “Alo, a bunch of police got shot. Come and see.”

White went in the living room and sat next to her. The reporter said the shootings had taken place on Neal Street. White knew it was in the Bluff, where he bought and sold drugs. Earlier that evening, in fact, the Atlanta narcotics police for whom he worked as a C.I., or confidential informant – a snitch – asked him to go to the Bluff and buy drugs. His car was in the shop, so he had to say no. His mother knew none of this.

Upstairs at his mother’s house, he had already received a call from J. R. Smith, one of the officers from the unit. Smith sounded tense. “Hey, you got to help us out with something,” White told me Smith said. (Smith did not respond to a request for an interview.) White said sure. He tried to be helpful to the police, do what they asked – willingness was one reason he was their most trusted informant for four years running. If White could help cover for them, Smith said, there would be good money in it for him.

“You made a buy today for us,” Smith explained. “Two $25 baggies of crack.”

“I did?” White asked. It took him a moment to register. “O.K. Who did I buy it from?”

“Dude named Sam.” Smith described the imaginary seller, told how Sam had taken his money then walked White to the back of the house and handed him the drugs as Smith and a fellow officer, Arthur Tesler, watched from a car across the street.

“O.K.,” White said. “Where?”

Smith said: “933 Neal Street. I’ll call you later.”

Now in the living room, the TV reporter was saying how a 92-year-old woman had died in the incident, and people were suggesting that the police had shot her. Two and two came together in White’s mind. They did it, he suddenly knew. They messed up. They killed that old lady. Now his heart pounded as the implications became clear. And they want me to cover for them.

White had lived near the Bluff, a neighborhood of Atlanta infamous for drugs and crime, for a year or so. Its residents are almost all black and poor. There are no row houses here, nor high rises; the housing stock is seldom more than two stories tall. Streets of small, well-kept houses alternate with streets full of junk-strewn, overgrown lots, abandoned houses and apartment buildings with broken windows and dirt instead of lawns. There is little that says money and much that says despair: semiabandoned commercial strips with hand-painted signs, bodegas with few products and fortified cashier booths, pit bulls on chains, groups of men hanging out on corners and behind car washes and outside probation centers, drinking beer or selling drugs. Police cars, often with lights flashing, are ubiquitous, but I never saw a police officer on foot. A stark contrast are the nearby enclaves belonging to prosperous black colleges like Spelman, Morehouse, Clark Atlanta University and Morris Brown College, their grounds immaculate and, to the local poor, effectively off-limits.

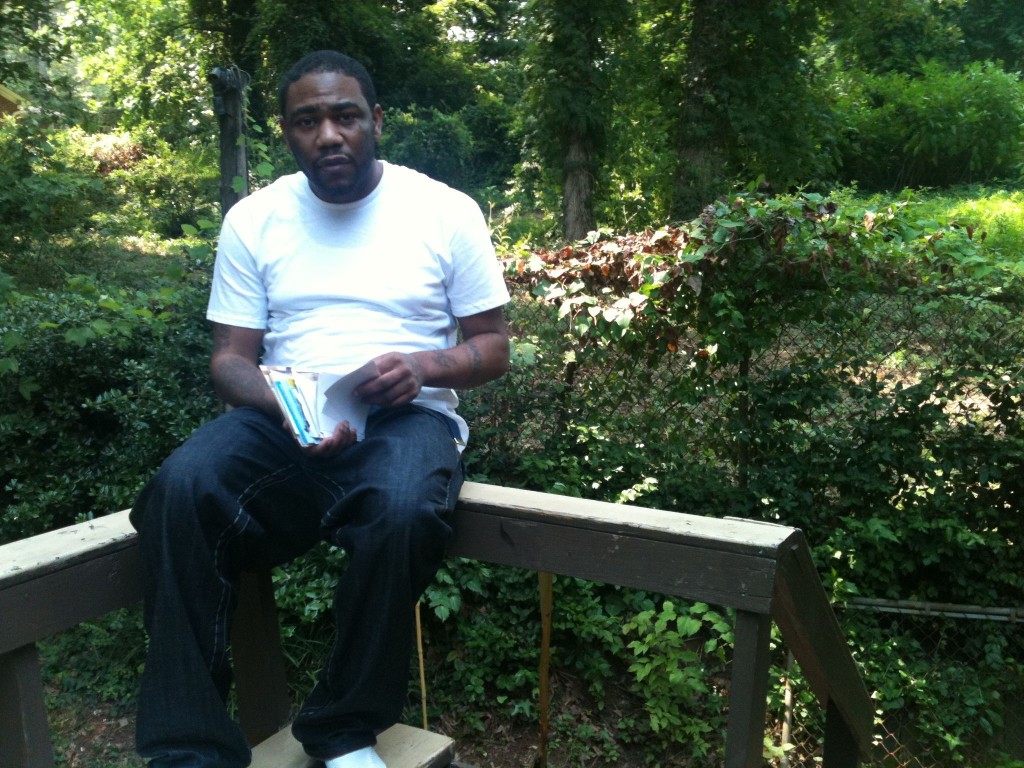

White, who is 30, is a big man, almost six feet tall, about 235 pounds, with a mustache, an easy smile and a gold incisor. (Girlfriends have noticed a resemblance to the rapper Nelly.) Inwardly suspicious, he is outwardly gregarious, charismatic and upbeat. He will happily shake your hand and immediately start in with what’s on his mind, looking away while speaking in the manner of an N.F.L. coach on the field who doesn’t want the camera to see what he’s saying; it’s confidential. Often his ideas have to do with making money; White is a natural-born hustler. Native to the Atlanta metro area, he grew up partly in Decatur, just to the east, and partly in what was the sprawling Bankhead Courts housing project, a 20-minute drive west from the Bluff.

Drugs, police and the questions of loyalty that arise when the two cross paths have been part of his social landscape since he was a child. One of his earliest memories is from age 9. “One day there’s an old-school dealer, about 40, named E. T., selling crack,” White told me in one of our many conversations over the last 15 months. “He kept his stash in a purple cup [from] Kentucky Fried Chicken. . . . I remember that cup plain as day. The police drove up, arrested him – they must have just had somebody do a buy from him – and put him in the car. I was standing around. They asked me what I was doing there. I said, ‘Nothing.’ ”

In fact, White had seen where E.T. was hiding the KFC cup in a pile of garbage nearby. Somehow the police knew to pressure White and, pretty quickly, he gave the dealer up. “Right then and there, I knew I screwed up – I screwed him,” he said. “But at that age, you don’t know how to lie to the police.” White was scared to see the dealer after that – until E.T. told him it was O.K., everybody makes mistakes when they’re young.

Though White doesn’t paint his family as impoverished, clearly there wasn’t much money to go around. His dad, a quiet, mild man, worked only sporadically, laying carpet, while his mom, who received a Social Security disability check for a nerve problem, took care of him and his younger siblings – Calandra, who’s now 28, and Kevin, who’s 18. When Calandra started having children at 16, his mother cared for them, too. “In the hood, it’s a struggle,” White said. “Your mom get a check at the end of the month, and ain’t $20 left three days later. There was money for what we needed but not for what we wanted.”

What he wanted would cost more than he could make at McDonald’s, where he worked briefly as a teenager. White hit the street to make up the difference. “He was always coming up with something new,” Trel Burnstine, his longtime friend, said. “He was always hustling, and I respect that, always the businessman. He would sell you anything.” He added: “Big-screen TVs (I still have one), cases of liquor, stuff stolen out of the back of trucks. He’s the ultimate hustler. He could flip anything.”

His mother told me: “When he first started getting in trouble was when he stopped going to school. He did nine months in boot camp when he was 15 – they said he stole some tools from a truck.” (White says he was sent away for selling drugs.) “But after three or four months, he went back to the same thing. I beat him, but it didn’t make no difference.”

When White was 17, he teamed up with Trel, and they sold drugs down the road from the Bankhead projects at a large Petro truck stop off Interstate 285, west of downtown Atlanta – marijuana, crack, powder cocaine. The rocks of crack cost “five in the hood, but they’re $15 or $20 to a truck driver,” White said.

In early 2001, in the truck-stop convenience store, White met Antrecia. She worked the register. Both were 19. “I had got out of high school and had just had my daughter,” Antrecia told me. “Alex came, and he said, ‘Let me take you out’ – he wasn’t driving nothing, he just tricked me. I said yes. I guess he was my first boyfriend. We started living together in 2002.”

White quit high school after 10th grade. He said he was academically gifted but saw bigger opportunities in selling drugs. He admired a kingpin named Demetrius Flenory – Big Meech – who controlled cocaine distribution in the region from the 1990s until around 2005 through an organization called the Black Mafia Family. Big Meech befriended rappers like Young Jeezy, held legendary parties at clubs and made a push for legitimacy with a music company called BMF Entertainment. White was nowhere near the Black Mafia Family inner circle, but he believes he distributed their product. Like others in Big Meech’s orbit at the time, he tattooed BMF onto his right hand, and one of its slogans, C.O.S. (Code of Silence), on his left.

To make money in drugs, you need a crew, and White started his own, which included Trel and White’s light-skinned cousin, Whiteboy, and some others. He says he was just starting to move the kind of volume that would let him get off the street and into a position of managing when he had a pivotal encounter.

It was a Saturday in August 2002, he recalls, not only because he has an excellent memory for numbers but because it was the same day as the annual reunion of past residents of Bankhead Courts – they met for a picnic every year in a nearby park. White planned to go with a friend. But in the meantime, he was catching some fresh air in front of the apartment he shared with Antrecia on Martin Luther King Jr. Drive in west Atlanta. An unmarked police car containing three detectives came up over the curb and screeched to a stop a couple of yards away. Always ready for this kind of thing (like most of his friends, he had been arrested a few times already for selling drugs), he subtly dropped a baggie of weed from his waistband down his pants leg and deflected it under a car with his foot.

The police put him against their car and frisked him. When he came up clean, they couldn’t arrest him but then they ran his ID and came up with an outstanding probation warrant – White had failed to return to court as part of the disposition of a marijuana charge. It was only a misdemeanor, but they handcuffed him and hauled him in. On the way, they started talking; White was friendly and outgoing. An officer wrote down his number, told White to call some day. White construed the offer as opportunity: the police, after all, were a main impediment to success in business. Some of his cohort hated them. But White was a pragmatist, and after his short stint in jail, he called the officer. This was a way to get ahead, he thought. Cooperating had a steep downside, namely that word could get out – in which case his reputation and even his life would be at stake. But he thought he could live with the risk.

A set of rules specified what White should have been paid for helping the cops bust people like himself and his customers: $25 for a marijuana buy, for example, and $35 to $50 for small buys of crack or cocaine. There was the chance of a big payout if an informant led police to a kilo of coke, but those chances were few and far between. Normally, money for snitches amounted to what White called “chump change.” He made his real money by running his crew on the street corners and by working the clubs at night, brokering sales: “A guy come in from out of town, I fix him up.”

But as the cops got to know White and vice versa, the unofficial possibilities became clear to both sides. White assumes the cops liked working with him because he was both well connected with drug dealers and easy to deal with; he could navigate both worlds. To White, working with the police was like adding a second business (informing) to his existing one (dealing). Betraying people seemed not to weigh on his mind. “I don’t set up people I know,” he said. “I only set up nobodies.”

His dream job would have been to be a real somebody – a top lieutenant of Big Meech or even Big Meech himself. But “I wasn’t plugged in like that,” White said, and so the police offered an alternative career path, albeit a less glamorous one. According to White, the police pocketed some of the money they confiscated during drug busts and sometimes shared it with him. White soon was earning more than he ever had: sums approaching $40,000 a year, he guesses, though he says he never really had time to count. He just knew there was plenty to go around: he bought Enyce jeans and Nike Air Force 1 sneakers for himself, wristwatches for his friends and crew and gold hoops and diamond necklaces for girlfriends. But the real money went to his mother and to Antrecia, his first love and on-again-off-again girlfriend of many years.

But Antrecia was no dependent. From truck-stop cashier, she became a hairstylist. She loved White, but she never thought of giving up her career – she liked knowing when she would be paid and knew that children needed constancy. Antrecia has long, straightened hair, wears contact lenses a light shade of hazel and is curvaceous. She doesn’t like to sit around: “There’s not one day I’m not doing something – I’m always on the go,” she said. She’s often working or trying to keep White in line. Half-seriously, she told me, “God put the woman on earth to nurture and guide the man.”

Their occasional fights, in her view, stem from the way that “we both like to be the best dressed, the center of attention. We both want to be right.” Knowing that White’s life was exciting but risk-filled, I once asked her if she ever tried to get him to pursue honest work, a regular job. Yes, she said, she had. “I’ve thought about that many times. But he’s too . . . hoodish.” With every new tattoo on his face, neck, hands or forearms, White proclaimed his gangster identity in a way that would make mainstream employment that much harder. In any event, working with the police (an arrangement Antrecia was privy to) was bringing White success beyond either of their expectations. With a steady job, high income and apparent immunity from arrest, he was doing very well.

According to White, some of the officers he worked with were particularly tough. Unlike the uniformed police of the Red Dog Unit (the name has come to stand for Run Every Drug Dealer Out of Georgia), White’s handlers were plainclothes and were free to roam the entire city in search of bigger fish. They ruled by intimidation and enjoyed manhandling those they ran up against on the street, White said. He saw them beat people and said that he was roughed up himself more than once when, in order to protect his identity (they said), the cops arrested him and slapped him around right along with all the real suspects.

The leader of the team of officers that he worked with most often, Gregg Junnier (pronounced “junior”), apparently set the tone. White said suspects would sometimes make the mistake of talking trash once handcuffed. Junnier would then slam them against a car or grab them on both sides of the mouth, supposedly to keep them from swallowing drugs. White remembers the time another officer he worked with had a suspect handcuffed and on his stomach; when the suspect began insulting him, White said, the policeman “kicked him in the mouth,” which made even his fellow officers flinch.

“One day Junnier come into my apartment,” White told me, “started throwing stuff around. He say, ‘Where’s the money?’ He knew I’d made some that week. He going through my dresser. He took $4,000. Junnier rough. He very, very rough.” White just accepted the situation. He was not a partner but merely a sub rosa subcontractor, a fact Junnier frequently reminded him of.

Junnier’s team drove around in a black Ford van with darkened windows that became notorious – Darth Vader’s own ride. “Everybody know that van,” White told me. Junnier also drove his own S.U.V., and one day he handed White, in the passenger seat, an envelope full of pictures.

“He show me this Jamaican guy,” White said. “Except only his head, on a fence. It had dreadlocks on top and veins below where it got ripped off. Junnier say he fell between buildings during a chase.” White said he felt he was shown the photo as a kind of warning. (Junnier, through his lawyer, denied all claims by White; the Atlanta Police Department would not comment.)

White knew the cops were dirty; he saw the corners they cut. He presigned cash disbursement forms so that the officers could fill them in as needed. The fact that White knew this perhaps gave him a bit of power, but in reality it frightened him: they were dangerous men to consider displeasing.

When White got the call from J. R. Smith the night of Kathryn Johnston’s murder, asking him to cover for the police, he knew he had to play along. But he also knew he was vulnerable: the police would spin the events whatever way helped them the most. To protect himself, he started taking notes. He wrote down the time Smith called and the number he called from. One of White’s slogans was “I may play dumb, but I ain’t never been a fool.”

His phone began to ring in earnest: Junnier, it turned out, was in the hospital, slightly wounded in the face and leg. (Not by Kathryn Johnston, it would eventually be revealed, but by bullets fired by other police officers.) Friends called, jubilant – they had seen the notorious cop’s picture on TV and were delighted by his misfortune; Junnier was widely hated by drug dealers. White was not sad about that side of it – Junnier had it coming. But White could see (though not admit to his friends, who were unaware of his sideline) that, if his handlers got taken down, this could be bad for him financially. And it would be bad for him in every way if they dragged him down with them.

As a low-rent secret agent of sorts, White couldn’t talk to many people about his situation. But there were a couple: Antrecia and an uncle. White also knew some federal law-enforcement agents. His reputation as a reliable informant had spread within the law-enforcement community, and he says he worked with the Atlanta office of the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (A.T.F.) on several busts of illegal gun dealers while fully wired and monitored by vehicles outside the meeting place – by the book, in other words. (The A.T.F. would not comment. White says he was also used by the Secret Service on a counterfeiting case; the Secret Service would not comment, either.)

According to an F.B.I. report assembled from interviews with numerous officers in the months that followed, White called his A.T.F. agent, Eric Degree, who drove over the next morning. After White unburdened himself, Degree advised him not to take calls from his narcotics handlers and to keep him apprised of developments. Minutes after Degree left, White says, Junnier, out of the hospital, called – and White, unable to resist, answered. Junnier wanted to go over the story that Smith and White had settled on and to make sure White was still with the program. “Uh-huh,” White said as he listened. Junnier said that detectives would be coming by White’s mother’s house to show him a photo lineup of people who could be “Sam,” the man who supposedly sold him crack.

White’s understanding of what happened next diverges from the account that can be pieced together in the F.B.I. report. White told me that he was worried that Scott Duncan, the narcotics detective who came by, could be in cahoots with Junnier, and had come to rehearse White’s agreed-upon story and to test his loyalty. The F.B.I. report, by contrast, paints a picture of a detective innocent of the cover-up, sent by superiors trying to find Sam.

The F.B.I. report confirms that Duncan and White met at an intersection near his mother’s house. White says that he never intended to get inside the car but that he did to remain inconspicuous when some young men drove by. And he meant to keep the door ajar as well, but in a moment of inattention, it clicked shut.

Once inside, the child locks were on, and he worried that he couldn’t get out. They drove to a vacant lot, where Duncan parked and had White tell his story while the car idled. Next they drove over to Neal Street. White grew increasingly nervous. They came to a stop outside the county jail. White said that Duncan and another detective in the car, who never identified himself, told him they were there to collect the photo lineup. But instead, they left him in the car while they stood outside and made phone calls that White couldn’t hear.

White called Degree of the A.T.F. – he wanted him to know the mess he believed he was in, and the danger. At one point, according to the F.B.I. report, Degree instructed him to pass his phone to the officers; he told Duncan that he needed to see White in his office when he was done. The detective replied that he needed to keep White for a while, that the photos weren’t ready, and handed the phone back. White, now increasingly paranoid, wondered whether he was going to be killed – that way he could never undermine the cover-up. His fear growing, he called Degree again. This time, he says, the federal agent told him that he had to find a way to get out of that car.

Whether or not that was his instruction – Degree’s statement in the F.B.I. report doesn’t mention it and the A.T.F. won’t say – it’s what White resolved to do. His chance came when the detectives stopped in traffic just opposite the Varsity restaurant, an Atlanta landmark near downtown. Though he couldn’t open the back doors, White found that the electric windows still worked. He lowered one and, before the detectives knew what was happening, opened his door from the outside. He escaped from the car, dashed across the street and ran inside the Varsity. The police, leaving their car in the middle of the road, jumped out in pursuit.

White exited the restaurant through a different door, recrossed the street and did what any frightened citizen might do: he dialed 911. The police recording captures a panicked White The police recording captures a panicked White telling a dispatcher that he is outside a gas station being pursued by cops “on the dirty side.” She responds, “So you’re calling the police, and the police are chasing you.”

White next called Degree again, and he and another A.T.F. agent responded in minutes. They took him to their office and called the Atlanta Police Department’s Internal Affairs unit, which dispatched officers to pick up White. Over four or five hours, White says, they subjected him to a polygraph test and had him call Junnier and others while they listened in. Late in the day – one of the longest of his life, he said – they drove him home.

Only minutes later, the phone rang again. It was Junnier. “I could hear he was sweating,” said White, who had the feeling Junnier knew he’d been to Internal Affairs. Junnier asked whether White was sticking to the story. “I said yes. But then he says, ‘Where are you now, man?’ And I said, ‘Oh, I’ll be staying outside the city tonight.’ And he says: ‘Yeah? Where you gonna be?’ I told him something different, but the whole time I’m thinking, Man, why he wanna know that?”

White, certain that he was a marked man, left an urgent voice mail for Degree and on the hot line for the local office of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. No one called back; it was the night before Thanksgiving.

At a big Thanksgiving dinner with family the next day, White could think of nothing but his terrible situation. Finally he confided in an uncle, who suggested that he go public – call the TV! This was a radical step, going outside law enforcement, leaving secrecy behind. It might create a new raft of problems for him, with former associates wondering, Hey, maybe that was the guy who set me up. But White concluded that raising his profile was his best chance for survival. The snitch would come in from the cold.

That night he called WAGA Channel 5, Atlanta’s Fox affiliate. The killing was still big news, three nights later, and they were very interested. To establish his credibility, White says he called Junnier yet again while a reporter and producer listened in. The next morning, he went to their studio in a taxi.

They offered to shield his identity, but White said: “Naw, we’re past that now. Use my name. Shoot me like I am.” (Ultimately they obscured his face anyway.) Once the taping was done, though, he hesitated to leave the station, worried about what awaited him outside. He ended up spending the day there, lunching with staff members and helping with further reporting into the evening. Finally, around 10 p.m., he took a call from an F.B.I. agent, agreed to meet him at a nearby parking lot and finally stepped out of the door.

In the meeting, he says, he outlined his fear, and the F.B.I. responded with a plan to house him outside Atlanta, as a kind of protected witness who would help prosecutors and investigators build their case. But he wouldn’t go for that. The city was all he knew; living anywhere else scared him more than staying put. They said O.K. and drove him to his mother’s, where White began to pack his bags.

The F.B.I. checked him into a series of business hotels around the city, White says, and encouraged him to stay indoors. He received a weekly expense allowance and could feel as if he were living large. (The F.B.I. would not comment.) But he soon tired of watching DVDs and felt isolated, lonely and low. He and Antrecia had always been an intermittent thing; now they were in touch, but apart. Fearful for his life as word spread on the street that he was a longtime snitch, he tried to stay away from other friends and family, too. He began to frequent a club called the Chit-Chat Lounge. He met a woman there named Xernona; it speaks to his unmooring that he abruptly married her.

Meanwhile, his semicelebrity grew. In January 2007, newspapers were still telling the story of White’s role in turning in the cops. Thinking he might have a legal case against the city, White had found a civil rights lawyer, Fenn Little, who filed a suit seeking damages for, among other things, his confinement in the detectives’ car the day after the shooting. Little helped White embrace a narrative for what had transpired: his client was a hero for turning in crooked cops. The lawyer knew that the suit was a long shot – and indeed, it went nowhere. But the hero idea endured with White; it offered clarity about his actions. The story was given a boost by the Rev. Markel Hutchins, an activist preacher and “media adviser” to the family of Kathryn Johnston. Hutchins, aiming to get national exposure for the family’s wrongful-death claim against the city of Atlanta, pushed for Congress to take up the issue of the overuse of informants. When John Conyers Jr., a Michigan congressman who was chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, announced in May that the committee would hold hearings on the matter, White was at his side. White said, “I came to Washington to make sure this never happens again,” and the headline in The Atlanta Journal-Constitution read, “Informant Warns of Police Abuses.” To get to Washington, White flew in an airplane for the first time in his life. He returned in July for the hearings. He wore a suit and tie bought for him by Little. White didn’t testify, but he sat behind Hutchins as he argued for shedding some light on a process that often took place in judges’ chambers, where the police presented information collected by informants.

But the hearing was the peak for White; beyond lay a steep decline. Soon after his Washington trips, important people lost interest in talking to him. In November, a year after the crime, a reporter from The Journal-Constitution tracked him down, just as he feared that those he’d ratted out might do: he had sown his city with personal land mines. If it seems odd that a person in hiding would talk to the press, it was consistent both with White’s desire to remain relevant and with his conclusion that notoriety was more likely to protect than imperil him.

“I’ve got to worry about the cops,” he told the paper. “I have to worry about the people on the streets [who sell drugs]. . . . It’s unreal thinking you’re going to die, wondering if you’re going to get framed. . . . I wonder, is my phone tapped? Are they following me? You know how easy it is to be set up when I’m by myself. That’s playing with my mind.”

He said he felt proud that he turned in the corrupt police officers so that justice could be done. But he said he often wished he had never spoken out. He “wanted to drift off,” he said. He “wanted to disappear.”

He told me later that he was “sleeping with a knife by my bed, because I can’t have a gun anymore” (because his F.B.I. handlers wouldn’t like it). And “selling drugs in the future is going to be hard, because the kingpins ain’t gonna want to sell to me.”

Meanwhile, investigators and prosecutors were working on their case against the cops with White’s help. Junnier and Smith pleaded guilty in state court to voluntary manslaughter and other charges and in federal court to a civil rights conspiracy violation that resulted in the death of Kathryn Johnston. Tesler, the only one to face trial, was convicted of making false statements in state court. (The conviction was overturned, and he pleaded guilty to the federal charge against him.) Junnier, the first to take a deal with prosecutors, received a federal sentence of six years. Smith, who was deemed the most culpable, received 10; Tesler, 5.

A civil rights leader, the Rev. James Butler, told me it was the first time that white police officers had ever been sent to prison in connection with the death of a black person in Georgia. Though I could not confirm that statement, Atlanta’s new police chief, George N. Turner, told me, “I’ve been here all my life, been policing almost 31 years, and I cannot recall another case where a white law-enforcement officer has gone to jail for violating any rights of a citizen.”

Late in the summer of 2007, after going to Washington and after about eight months of living in hotels, two things happened. One was that White left Xernona and rekindled his romance with Antrecia, who was now living with her two children and styling hair in Douglasville, a conservative suburb just outside the Atlanta city limits. The other was that the F.B.I. stopped supporting him, he says. He says he didn’t know why, and the F.B.I. won’t comment, but acquaintances have said he was using his government money to stake himself to a fresh start selling dope.

White admits that he was selling marijuana at the time. At one point, a guy he met at a regular Friday poker game at T.G.I. Friday’s in Douglas County was pestering him to sell him some pot. White smelled a rat but, for reasons he has a hard time explaining, decided to play with him. He appeared to believe that, as a rat extraordinaire, he could recognize a trap and stay out of it. Over days and weeks they danced back and forth until, eventually, White sold the man a couple of ounces of marijuana.

The transaction was secretly recorded. Douglas County has some of the toughest drug enforcement in Georgia; White could scarcely have picked a worse place to get caught. When he was brought to the station, the Douglasville Police taped an interview between a lieutenant and White. On the tape, toward the end of the interview, friendly but with a note of desperation in his voice, White asks, “There is nothing I can do?” The lieutenant responds that it is out of his hands. Two years after the death of Kathryn Johnston, White, snared by an informer like himself, began a sentence of up to eight years in state prison.

Prison is a bad place for dirty cops and police informants. They are at risk from other prisoners – even somebody with no personal grudge can enjoy the status that comes from “offing a snitch.” White spent most of his sentence in protective custody, which basically means isolation, the box, an individual cell in a high-security building where there’s no group exercise, no eating together. That kind of privation takes a toll on many people. But White seems to have done all right.

Last summer, he was paroled after two years and five months. A cousin, who the month before finished a 10-year sentence for armed robbery, picked up White at the bus station in Atlanta. I caught up with him the next day. He had gained some weight and was less fit than he was when he went in, but he was still outgoing, still animated, still talkative. For a man stuck alone in a cell for more than two years, he exuded surprising charm.

White’s parole seemed more like house arrest: he would live at his Aunt Ree’s, where he had to be in every night by 9 for the next five years, unless he found a job, in which case the curfew could extend to midnight. But legitimate jobs are hard to find when you are an ex-con. He was finished as a snitch, and further drug dealing on any scale was at this point impractical – if he were caught, he would face considerable time.

The first weekend he was back from prison, his family gave a big party at Ree’s – a barbecue. People prepared for it over at least two days: White’s mother made potato salad and beans and readied ribs for grilling; Ree looked after the chicken; others took care of the corn on the cob and refreshments. Nearly a hundred people of all ages passed through the family’s house and yard before it was over. Antrecia – whom he married before his sentence began “so I wouldn’t lose her” – couldn’t attend, but his ex-wife Xernona did. Initially nervous when he saw me talking to her, White relaxed as the night went by. I asked Xernona what his best quality was. “His sweetness,” she said. And his worst? “Too nice.”

I thought seeing so many people after so much time in isolation would overwhelm White, but he seemed energized. Only two parts of the evening seemed difficult for him. One was when some young men he knew arrived in a tricked-out Dodge Charger with custom wheels and paint. They were dressed in upscale hip-hop fashions: gleaming white sneakers, baggy jeans, designer sweaters and name-brand baseball caps, necklaces and rings. “Oh, man!” exclaimed White as they greeted him – his wardrobe had been only slightly upgraded in the past four days, and he was still borrowing his younger brother’s cellphone. White looked at the car and the clothes. Light on their feet, they smiled and laughed. “When you got no money, you got no power,” White would say later.

The other difficult moment was around 11 p.m. when a group of young people, including his brother and some cousins, left the party to walk to a nearby park. White desperately wanted to go, but his parole required him to stay at home. I watched White watch them walk away into the dark, trembling with excitement but restrained, as though behind an invisible electric fence, longing to advance but mindful of the consequences.

“I’m still hiding, I’m still not doing the things I used to do,” he said. Not living life on the street, he meant, not hustling and not hanging out. He was stymied by parole. But when I saw him slouch down in his seat as we drove through the city and refuse to go into certain stores or restaurants, I knew that he was also afraid. Now he was completely stuck, unable to publicly function in any of his signature ways.

On another day, not long after his release from prison, White wanted to show me the landmarks of his old life. A few acres of grassy fields behind a fence, with pieces of foundation here and there, were all that remained of Bankhead Courts, his childhood housing project; it was razed while he was in prison. Before meeting her for lunch at a Mexican restaurant, we drove by Antrecia’s salon in a down-at-the-heels strip mall.

For dinner on a different evening that June, we ate hot dogs in the drive-in section of the Varsity restaurant. White wanted me to see where he fled the police car and where he called 911, but he was also on a public-relations campaign. Some people remembered him simply as a snitch in league with the cops who killed Kathryn Johnston. They didn’t remember that he was the one who turned the bad cops in – that he was the hero. He wanted me to see what our waiter would say, when White asked if he remembered “that lady that was shot by the police five years ago. And do you remember the guy who gave them up?” The man’s face lighted up: yes and yes. White introduced himself, pleased.

The problem with the hero claim was that, in some people’s minds, White’s turning against the cops may have just been a way to avoid being charged as an accessory to the killing, if the cops had been caught. He did the right thing, but it could also be viewed as the self-interested thing; it was hard to know. You could not be a snitch without having what could be called a flexible moral view.

Indisputably, he had done some good. The narcotics unit of the Atlanta Police Department was dismantled and rebuilt. A citizen’s review board was established to oversee the police. In Washington, White helped to raise awareness of the perils of law enforcement’s heavy reliance on informants and on the need for scrupulous oversight. Johnston’s family settled its civil suit against the city for $4.9 million in 2010. (The family was then sued for a share by the Rev. Markel Hutchins, who claimed they reneged on a promise to pay him.)

The future still looked hazardous for White. He claimed not to be concerned that Tesler would be released from federal prison in September and Junnier in February. “I ain’t gonna lose no sleep on it,” he told me last month. “They [are] like me now – they ain’t officers no more. They ain’t gonna take no chances.”

More pressing, on a daily basis, was simply the challenge of managing the remaining four and a half years of his parole. Since his release from prison, White had found a couple of days’ labor in warehouses and some regular work cleaning up for Antrecia; he also sells caps and T-shirts at a flea market. He moved in with Antrecia for a week before they declared it a failed experiment, and he returned to his Aunt Ree’s basement; nevertheless, they remained close, and she still liked using his last name. In his gloomier moments, he said things like: “There ain’t much to do but stay outta the way. Sometimes I feel like I’m still in prison.” Other times, he would declare his intention to reclaim his life and reputation. He added a defiant signature to his texts: “Refuse 2 B Forgotten.”

Our last stop as dusk fell that same June night was 933 Neal Street. Kathryn Johnston’s house has achieved the status of an urban shrine. It is boarded-up and abandoned but nevertheless looks well cared-for; stuffed animals and plastic flowers adorn the yard of what used to be just the home of one old lady.

We parked in front. The wheelchair ramp was still there. White pointed out the mural painted on the plywood over the front window: there was Johnston’s kind face. She is life-size in the painting, wearing a blue dress and glasses, smiling as she gazes out the window onto the street. The room the artist imagined looks cozy, with an orange rug, slippers peeking out from under the bed and a portrait of a man wearing a shirt and tie on the wall; it’s easy to picture Johnston looking out her window at life on Neal Street on the day the devil arrived at her front door.

Uneasy and self-conscious about his just-out-of-prison clothes – T-shirt, khakis, cheap sneakers (Antrecia hadn’t taken him shopping yet) – White wasn’t sure if we should get out of the car. We looked out at a handmade sign affixed to the wheelchair ramp:

Ms. Kathryn Johnston’s last hour

By bullet shower howls as our . . .

City cowers w/sour weed & seed

For loose-cannon police greed firepower!

Three middle-aged women sat in lawn chairs on the driveway next door. White suggested I hang back, then greeted them and introduced himself. I could hear as he started explaining. He wanted them to know who he was, wanted to make sure they understood he was the one who implicated the police in the killing. White waved me over and introduced me.

One of the women, Connie Jones, reassured him. “You ain’t did nothing wrong,” she said. “You told on the police!” She turned to her friends and said, “It could have been any one of us.” They nodded. White made sure I was writing this down. This was how the world would know that, after doing some wrong things, the hero had done the right thing. As White put it to me later, “When they get to the end of the story, they gonna see the man still standing.”

Ted Conover is the author of “Newjack: Guarding Sing Sing” and “Coyotes.” He teaches at N.Y.U.’s Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute.

Editor: Ilena Silverman