The Routes of Man

Travels in the Paved World

Book

From the book jacket:

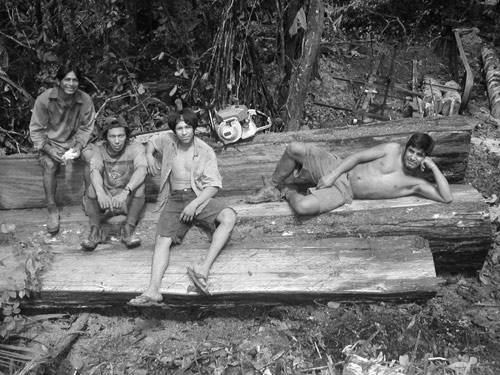

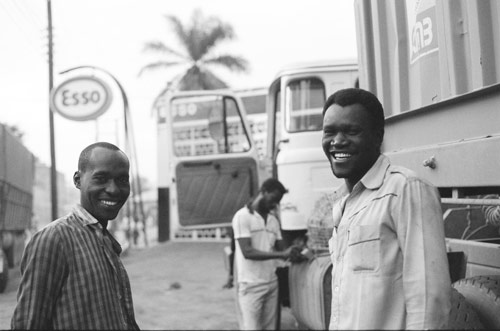

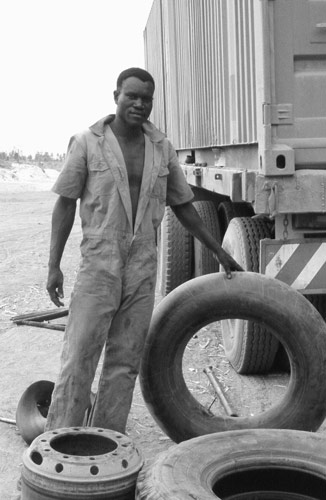

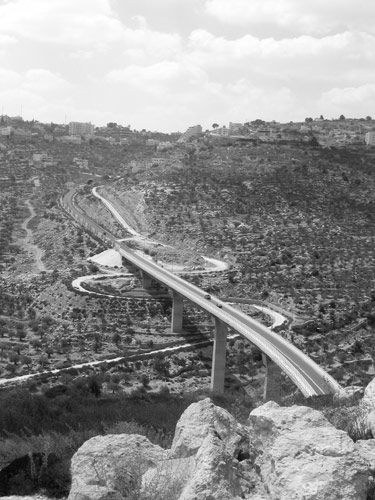

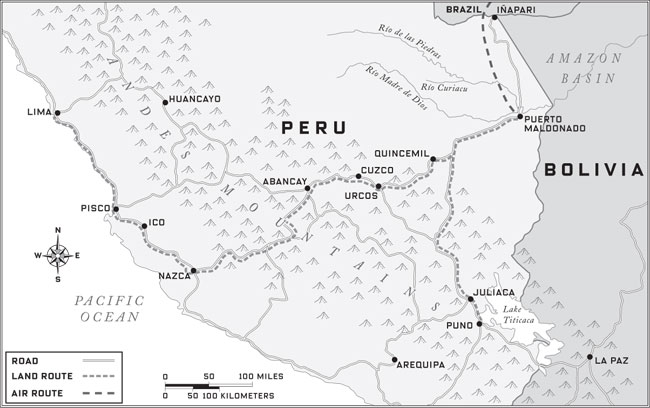

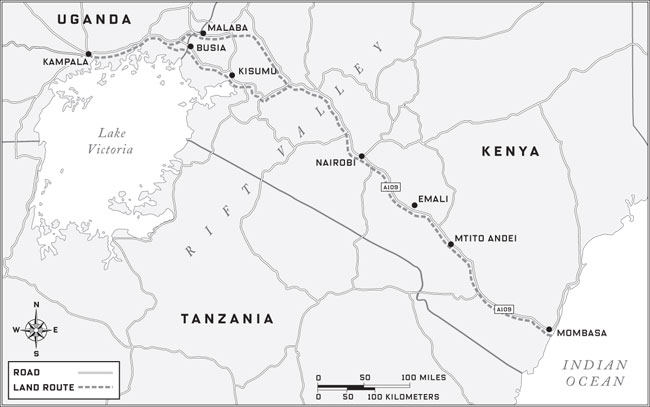

Roads unite people and sunder them. They both bind cultures across continents and highlight our differences. With his unrivaled passion and his famous eye for detail, Ted Conover explores six of these key byways worldwide: in Peru, East Africa, China, Nigeria, the Himalayas, and the West Bank. En route he introduces readers to intriguing characters and addresses some of the world’s most pressing issues–from the spread of AIDS by truckers in East Africa to smuggling along Peruvian highways. Throughout we see Conover’s remarkable ease with language, his infectious enthusiasm, his intrepid nature, and his deep humanity.

Reviews

“As I read this book, I grew increasingly impressed not only with Conover’s bravery and hardihood, which he underplays, but, more important, with that quality one associates with Steinbeck: heart. Here is a man who cares about people everywhere, not merely that convenient abstraction, humanity, but people in particular . . . The six road situations he describes are undeniable quandaries, and we owe it to the people caught up in them, not to mention to our planet, to consider what policies, if any, should engineer the roads through everyone’s lives.”

– William T. Vollmann

“Ted Conover is one of the great writers of my generation, and this may be his finest book. Fearless and compassionate, with echoes of Conrad and Kerouac, it explores how the road, once a symbol of limitless possibility, has become a path to annihilation. I have enormous admiration for what Conover has achieved.”

– Eric Schlosser

“One of Mr Conover’s previous books, about being a corrections officer in Sing Sing prison, was a finalist for the Pulitzer prize, and it is easy to see why. He has a wonderful eye for detail and the easy, unshowy style that marks the best travel writing. … Like the hoboes he met on the railways and the Mexican migrants of his earlier book, Mr Conover here has taken an unpromising subject and turned it into a book that is about far more than just the strips of tarmac that criss-cross the world.”

– The Economist

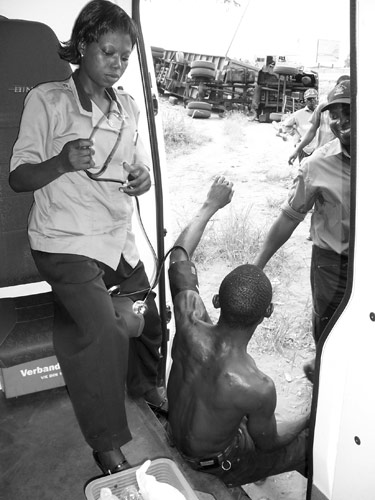

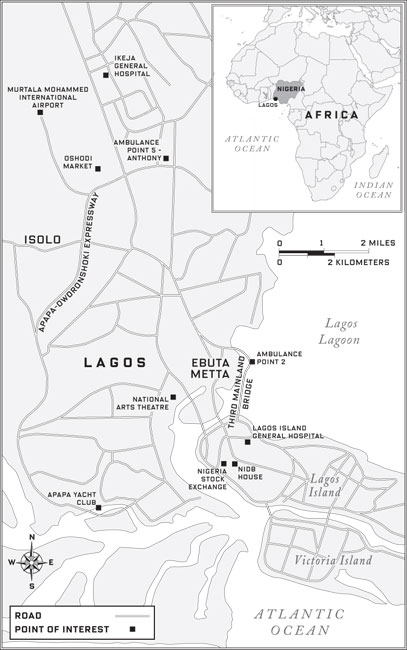

“Ted Conover’s exploration of six far-flung ‘roads,’ from a truck route over the Andes to an ambulance crew’s rounds in Lagos, Nigeria, will prove a delight, while at the same time serving to remind that in many places of the world the act of getting around is an art marked by pride, lust, corruption and bloodshed.”

– Erik Larson

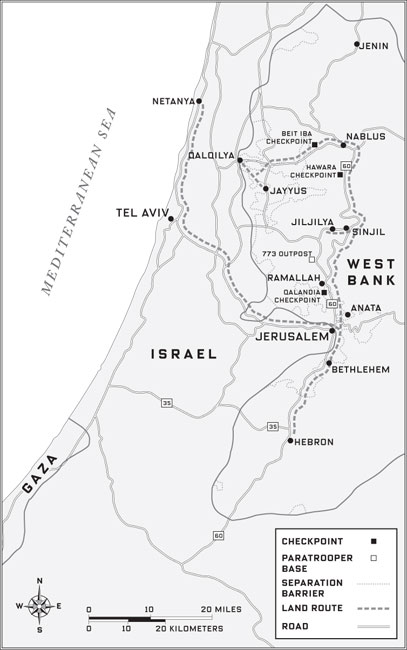

“Conover’s voice is that of a sobered Kerouac, tamed by a bigger conscience, and on an open road increasingly controlled by corporate, government, and military interests. His acclaimed narrative gifts are on full display in a wonderfully evenhanded treatment of the roadway in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. … Conover maintains a commitment to accurate portrayal and embraces the whole world, not only its dramatic aspects.… This many-textured journey is not to be missed. Conover deftly navigates the romance and harsh reality of a world intent on a real and not just a virtual connectedness.”

– Jeb Brugmann

“Conover’s voice is that of a sobered Kerouac, tamed by a bigger conscience, and on an open road increasingly controlled by corporate, government, and military interests. His acclaimed narrative gifts are on full display in a wonderfully evenhanded treatment of the roadway in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. … Conover maintains a commitment to accurate portrayal and embraces the whole world, not only its dramatic aspects.… This many-textured journey is not to be missed. Conover deftly navigates the romance and harsh reality of a world intent on a real and not just a virtual connectedness.”

– Taylor Antrim

Excerpt

From the Introduction:

He used often to say there was only one Road; that it was like a great river: its springs were at every doorstep and every path was its tributary. “It’s a dangerous business, Frodo, going out of your door,” he used to say. “You step into the Road, and if you don’t keep your feet, there is no telling where you might be swept off to.”

—Frodo Baggins of his uncle, Bilbo, in J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Fellowship of the Ring (The Lord of the Rings, Book One)

Every road is a story of Striving: for profit, for victory in battle, for discovery and adventure, for survival and growth, or simply for livability. Each path reflects our desire to move and connect. Anyone who has benefited from a better road—a shorter route, a smoother and safer drive—can testify to the importance of good roads. But when humans strive, we also err, and it is hard to build without destroying. Robert Moses, the controversial creator of highways around New York City in the middle of the twentieth century, wiped out numerous neighborhoods with his projects, turning vibrant communities (notably the South Bronx) into wastelands that have yet to recover. Of his actions he famously said, “In order to make an omelet, you’ve got to break a few eggs.” In a related way, the same roads that carry medicine also hasten the spread of deadly disease; the same roads that bring outside connection and knowledge to people starving for them sometimes spell the end of indigenous cultures; the same roads that help develop the human economy open the way for destruction of the non—human environment; the same roads that carry cars symbolizing personal freedom are the setting for the deaths of more people than die in wars, and of untold numbers of animals; and the same roads that introduce us to friends also provide access to enemies.

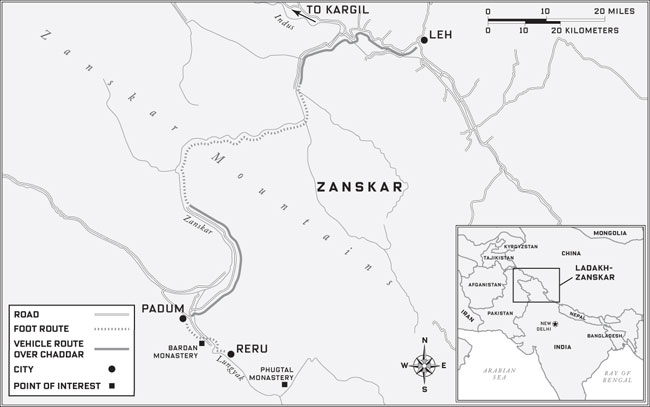

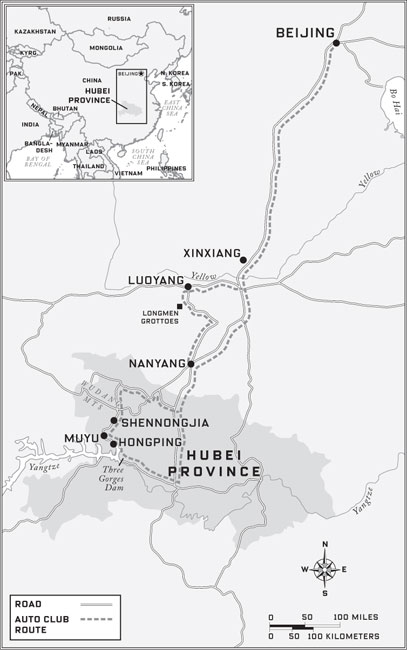

In this book I present six of these roads that are reshaping the world. I do it by joining up with people on them—travelers to whom they matter in an immediate and practical way. The roads are presented roughly in order of increasing complexity—which is also the intentional order in which I traveled them over the past several years. Each has a theme: development vs. the environment, isolation vs. progress, military occupation, transmission of disease, social transformation, and the future of the city. Not each of the chapters is about a single road, precisely; one tells about a trip on a series of roads in China, and another about roads and streets in Lagos, Nigeria. Each is a story and a meditation.

* * *

We in the twenty-first century are more numerous and better connected than people at any previous time in history. Networks are a principal theme of our age, and as the networks we are a part of continue to grow, we struggle to understand what that connectedness means. Not all connections are good. We save hours or days when we fly; yet it was the globe-hopping of a single promiscuous flight attendant that got the AIDS epidemic off to a fast start. We are threatened by terrorist networks such as Al Qaeda. The complex integration of the electric power grid, in North America as well as other parts of the world, means that a failure in suburban Ohio can black out large sections of the Northeast, the Midwest, and Canada, as happened in 2003, Politics and financial markets in one corner of the globe can affect financial markets everywhere. On a small scale, this means that a rebel attack on a Nigerian oil pipeline can cause a spike in world prices that will be reflected at the pump within days. Writ large, this means that a mortgage crisis in the United States can devastate financial markets around the world. Connection means vulnerability.

But most of our networks, most of the time, appear to advance human progress, leading to greater efficiencies and broader knowledge. We realize, for example, that we are part of social networks that extend far beyond our immediate circle of friends. (John Guare’s play Six Degrees of Separation popularized the notion that everybody on the planet is connected to everyone else through a maximum of six intermediaries.) The extension of social worlds beyond a network of local friends is greatly abetted by electronic communications networks—wired and, increasingly, mobile telephones and text messages, and, most transformative of all, the internet with its e-mail, instant messaging, and World Wide Web. E-mail, instantaneous and practically free, seems overnight to have supplanted first-class mail, a staple of the postal network that only two or three generations ago was itself a transformative network.

Have electronic communications rendered road networks less important? Hardly. Our inner circle of friends, our home communities, are still connected by roads. Everything real, by which I mean everything nonvirtual—food, furniture, goods of every description (including computers, I should add)—might be ordered online but they actually arrive overland, by train or plane, perhaps, for some of their journey, but always substantially by road. (The bumper sticker you see on trucks reminds us: “If you’ve got it, a trucker brought it.”) Roads remain the essential network of the non-virtual world. They are the infrastructure upon which almost all other infrastructure depends. They are the paths of human endeavor.

* * *

Being on the road is one of the ways I have always felt most alive in the world. Road travel has been a main story of my life, beginning with bicycle tours in the years before I could drive, intense pleasure in getting my driver’s license, and road trips and hitchhiking after I had, mainly during a college career that involved a few detours. One of these was a few months’ living with railroad hoboes—professional itinerants, essentially—in an experience that I turned into my first book, Rolling Nowhere. After graduate school it was back on the road for a year, in Mexico and the United States, with Mexican undocumented migrants, travels that became the basis of my next book, Coyotes. Higher education; road trip; higher education; road trip—the alternation was not coincidental. While I have benefited enormously from formal education, it has never seemed to me sufficient; it has repeatedly sparked in me a visceral longing for the lessons of life outside.

What’s that all about? College to me, particularly at the beginning before I figured out how to use it, was about imposed learning. Travel, on the other hand, was an expression of personal curiosity, of a broader education less mediated by received thought, It was also a test of personal resources beyond essay-writing cleverness and the capacity to handle course-induced stress.

And travel on roads seemed especially the right kind. Growing up in the American West, I had the idea that coming of age meant leaving the city, being tested in a place that was a little bit wild. Roads were the West in certain ways—civilized and yet often remote and unsupervised. Without question I was influenced by the ethic of the Beat and hippie generations that came before me, which saw travel as a masculine prerogative, if not duty. Kerouac’s On the Road, with its celebration of movement and its equation of travel with poetry, got under my skin; the day I left my aunt Janet’s house near Morristown, NewJersey, to begin hitchhiking west on my hoboing trip (Kerouac and I had New Jersey aunts in common), I remember Jan happened to be playing on her eight-track Glen Campbell’s “Gentle on My Mind” (“It’s knowing that your door is always open / And your path is free to walk”). Like so many songs of the day—the Allman Brothers’ “Ramblin’ Man,” the Temptations’ “Papa Was a Rollin’ Stone,” and the Grateful Dead’s “Truckin’”—it extolled the spirit of the travelin’ man, of unfettered life on the road.

Of course it goes back at least to Walt Whitman, the great American poet of the road. When I first read “Song of the Open Road,” I knew that we were from the same place. The speaker of this poem is happy to be going, glad to meet those he encounters (he lists them at length), rapturous at the journey and its possibilities, his travel a celebration of populism and democracy.

From this hour I ordain myself loos’d of limits and imaginary lines,

Going where I list, my own master total and absolute,

Listening to others, and considering well what they say,

Pausing, searching, receiving, contemplating,

Gently, but with undeniable will, divesting myself of the holds that would hold me.

I inhale great draughts of space;

The east and the west are mine, and the north and the south are mine.

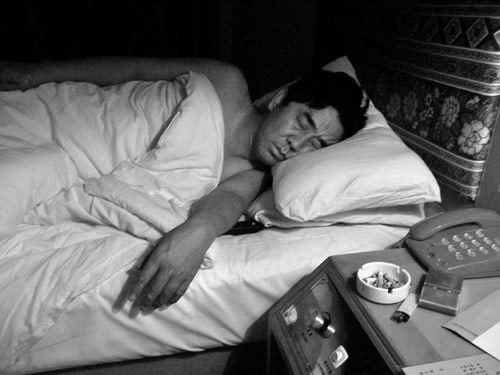

My last book, Newjack, was about working as a guard at Sing Sing prison. One night I was part of a transportation detail, relocating to a different prison upstate a gang member who’d been involved in a brawl. For me, it was a rare opportunity to work outside of prison walls. For him, it was a rare opportunity to see the outside world. Our van pulled over for dinner at a service area on the New York State Thruway. I brought some fast food to the prisoner in the van and we talked while we ate. He kept looking over my shoulder to the big trucks he could see parked outside, the semi rigs, and as one pulled out, he told me, “That’s what I want to do when my bid’s done. Drive one of those things.”

His wish made all the sense in the world. Roads are in so many ways the opposite of prison. Once I was finished wearing that uniform, I wanted to get back on them, too.

* * *

Almost 1.5 percent of the surface area of the continental United States—an area about the size of Ohio—is now covered with “impermeable surfacing”: roads, parking lots, buildings, and houses. Roads constitute the largest human-made artifact on earth. American landscape architect J. B. Jackson concluded in 1980 that roads are “now the most powerful force for the destruction or creation of landscapes that we have.” The siting of roads determines patterns of settlement, the locations of houses and businesses. The speed of cars upon them plays a role in how far from the road a structure will be: the older a dwelling in this country, it seems, the greater the likelihood that it was built near a roadsometimes right next to it, as in the case of my wife’s family’s farmhouse in New Hampshire. Horses and wagons were the traffic back then, and you had plenty of time to see them coming. These days the road is paved, and the cars whizzing by feel a little too close.

A road can change a shoreline, offering motorists great views but restricting access for pedestrians. A new highway can bypass a little town, killing its main street, or bisect a neighborhood, killing a sense of coincommunity. A father at my kids’ school declared to me bluntly that .is an ecologist he is “against roads,” and I know he is not alone: for those whose focus is protecting nature, roadless areas have a status approaching sanctity.* It Is not hard to enumerate the ill effects of roads. As roadbuilding continues its global acceleration, and the car hunger of Indian and Chinese consumers pushes global car ownership into the hundreds of millions, those of us in nations whose roads are well advanced (and a few of those in nations where they’re not, such as Amazon tribespeople threatened by roads) wonder whether there’s a limit to how much pavement and driving the earth can stand—how long, in the words of Joni Mitchell, you can “pave paradise and put up a parking lot.”

And yet, without roads and cars—or a viable alternative, which has yet to appear—afl human progress, all economic activity, would stop. The kids need to get to school, Mom and Dad to work, food (and everything else) to market. Watching roads can be a way to look at history, to measure human progress and limitation, In the past century, the global road network has become a thing that might finally, truly, impress the Romans. With near unanimity, we proclaim their usefulness. They are the human world’s circulatory system.

Where are they taking us?

© Ted Conover