May 22, 2012

Rehab

Newjack: Guarding Sing Sing is still considered contraband in New York state prisons — at least until the seven pages deemed a threat to security back in 2000 have been torn out. But though my book can’t come in whole, it appears that, as of last week, I can.

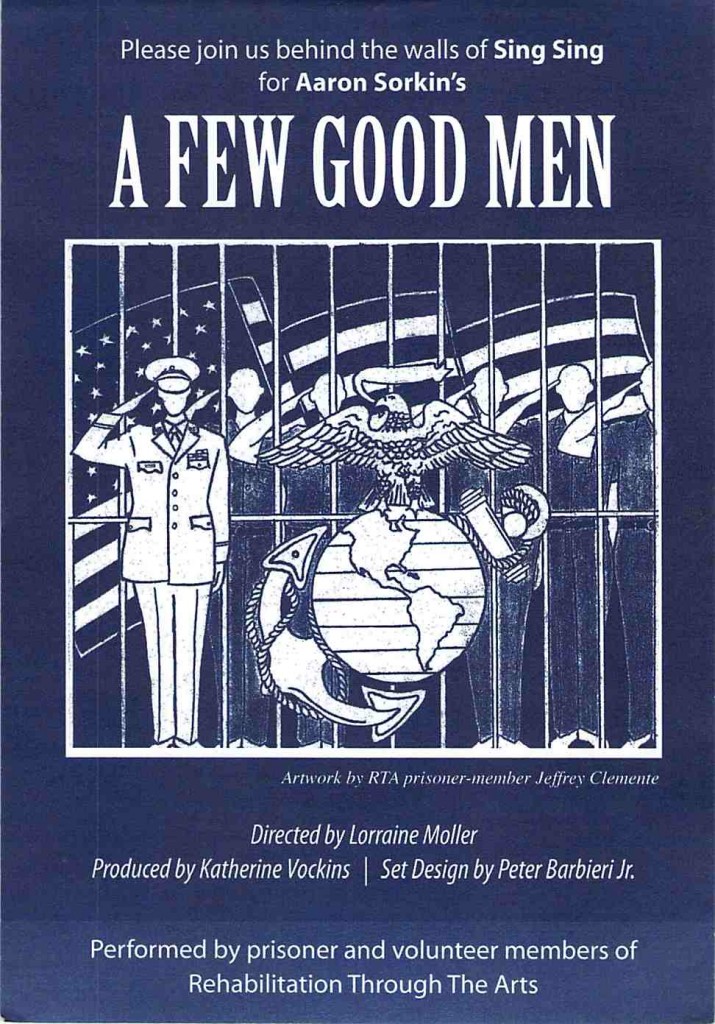

Rehabilitation Through The Arts, which helps stage a play at Sing Sing every year, invited me to see the inmate production of “A Few Good Men.” To my surprise, Sing Sing approved my visit and then Albany said okay, as well. I was rehabilitated, politically speaking — and last Friday, for the first time since I turned in my badge in 1998, I passed back through the prison gate.

Almost 300 civilians gathered in the prison theater — the only time all year so many outsiders are allowed inside. At least one was a professional actor from the outside world — Josie Whittlesey, who played the sole female part, a military lawyer. My wife and I pegged the male lead as another import — he had real star wattage, and we guessed maybe he came from some Westchester high school. (“This will help him get into Princeton,” Margot speculated.) After a moving performance and a thunderous ovation, the cast was allowed to shake hands and chat, from the stage, with the audience down below. Both sides were elated … and I must say, I’ve never felt more joy inside a prison.

As vans ferried audience members back to the prison gate, passengers were saying things like what talent! and what are these men doing in prison? Margot was particularly interested to know more about certain members of the cast, including the “high school student.” At home, I cross-referenced names from the playbill with the state’s inmate lookup site. Among the actors’ crimes were RAPE 1ST, CRIM POSS WEAP 2ND, CRIMINAL SEXUAL ACT 1ST, MURDER 2ND, ROBBERY 1ST, MANSLAUGHTER 1ST, AGGRAV ASSAULT/PEACE OFF., ATT MURDER 1ST. Some of those were committed, I’m afraid, by the same guy we pictured headed to college.

Margot was disbelieving. I didn’t have an easy answer for her, other than to remind her how many times I’d been surprised to learn the histories of men I supervised as a C.O. The costumes and the drama of the theater had made it easy for the audience to see them as somebody else. I think it probably did the same for the men themselves: for a few hours they could imagine themselves as different people, in different clothes, leading a different life. I can’t think of a better way of explaining rehabilitation — not my kind, but the truly important kind — than that.

The arts are first to go when education cuts need to be made, yet they can be an access point to not only the creativity and esteem of young people, but the rest of their studies as well. Invite a kid work to act out a character, or color the setting of a story he is struggling to write, and watch the words follow. Diverse learning styles can thrive when arts are incorporated and “low performers” can find footing.

Perhaps this is naive, but it makes me wonder what a sound arts program might have done for some of those men before they ever got to prison.

Thanks, Ted.

As you point out in Newjack, the ‘slow push’ toward rehabilitative programs at Sing Sing never came to much–and the drift of almost all correctional facillities in the country has been a steady abandonment of programs and activities that would help integrate prisoners to the outside world, once (and if) they make it there.

This to me is a badly misguided approach, and a practice that makes everyone suffer: prisoners, guards, relatives and the society at large. I agree with you: the play you describe seems a pure and moving kind of rehabilitation. Even if a prisoner is going to spend the rest of his life behind those bars, any rehabilitation, no matter how small or ‘personal’, is something that helps us all.

Ever see a short film called “The World’s Most Fashionable Prison,” about a maximum security prison (though it looks more like minimum-security in the film) in the Philippines, at which a gay fashion designer works to put on a runway competition? Fascinating.

I’m sure that putting on any kind of play or program at Sing Sing must be difficult these days–but I loved this story.

Thank you, Ted, for your story. My own experience as an actor and a director in a prison theatre program has absolutely convinced me that this work is a humanizing force for everyone involved.

For more information on prison theatre programs across the U.S., I recommend:

The Prison Performance Network

http://prisontheatreconsortium.blogspot.com/

The Shakespeare Prison Project

http://shakespeareprisonproject.blogspot.com/

Thank you, Ted, for all you have shared. Your work has been a valuable source of support and encouragement to me and my efforts.

I first read “Newjack” three years ago when I was first enrolled as the registered volunteer Wiccan/Pagan priestess in Auburn Correctional Facility. I held that postion for two years, as well as several months at Livingston and Groveland facilities.

I initiated to program to explore the effects of 200 years of accumulated “negative energy” within the walls of the facility: brutality, insanity, murder, suicide, deprivation all of which conspired to erode the human spirit. Not to mention the electric chair was invented here and used to execute 55 people over the course of 25 years.

This was the legacy of the regime of Elam Lynds who left Auburn to create Sing Sing.

Auburn’s other legacy was the reform efforts of Thomas Mott Osborne, whose torch was picked up by Lewis E. Lawes.

Wiccan/Pagan ritual is good theater. It is a portal which inmates may traverse periodically to experience inner healing and freedom.

As a child-Pagan in training, I learned the hard lesson that to put a hummingbird in a cage to keep as a pet, results in the death of the hummingbird.

I refer to that experience in choosing the title of my book about my own prison experiences and observations: “Magick in a Cage.”

Osborne said, at the inception of the Mutual Welfare League, “When you treat men as animals, they behave as animals; when you treat them as men, they behave as men.”

I contend the system as it exists is designed to contain and punish; there is no vision for healing, atonement or redemption.

Hi Ted,

‘Holding the Key’ is on the floor beside my bed at the moment, I’m re-reading it after re-reading Rolling Nowhere. Sometimes it’s nice to keep in the wheel ruts of a particular voice you’re enjoying even if the pages have run out…

I hear on the news here in New Zealand tonight that two prisoners have climbed a tower. They cannot escape, have no demands (or food or water) and the authorities seem flummoxed as to their motives.

As part of my head is in your book however, I think I understand: They are desperate for something novel in their restricted lives and are probably relishing the break in routine and may also be enjoying the different view.

Thank you for your books,

Gavin