November 23, 2010

The Pathetic Newburgh Four

Few tasks would appear as urgent for domestic intelligence as monitoring sources of homegrown terror. Nipping plots in the bud will inevitably entail the use of informants, as cells are clandestine and must be infiltrated. And common sense suggests that, when it comes to the search for bad guys, some zip codes will be of greater interest to the FBI than others.

Americans appear to be nearly unanimous in our support for the above. And yet, should we accept the tawdry results of this effort so far? Why does the government’s anti-terror net catch such unconvincing villains: black men near mosques who, in exchange for promises of money, sign on to knuckleheaded schemes that would never exist if it weren’t for the informants being handsomely paid to incite them? (Update, Nov. 29, 2010: The latest addition may possibly be Mohamed Osman Mohamud, the 19-year-old naturalized American citizen from Somalia whom the FBI arrested Friday and charged with plotting to set off a bomb in Portland, Ore.)

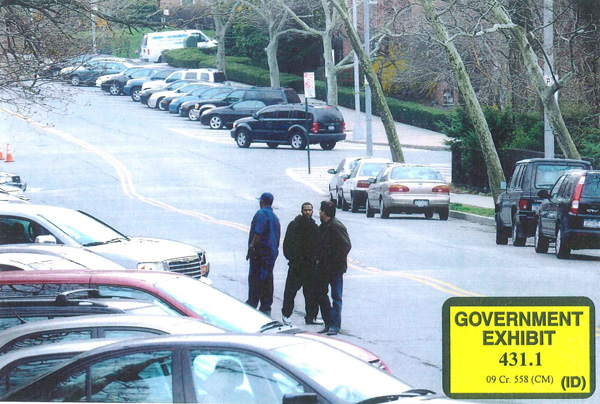

These prosecutions fail the smell test, and lately the odor has washed over my own Bronx neighborhood of Riverdale. Last month, if you missed the news, four African-American ex-cons from Newburgh, N.Y., were convicted of plotting to bomb two synagogues here, one of them half a block from my house. The government released a photo of some of the men casing the joint that our local paper ran the day they were convicted.

One of the men in the photo is an FBI informant, Shahed Hussain. The case seems like a slam-dunk–until you learn more about him. Hussain, driving a flashy Mercedes and using the alias Maqsood, began to frequent the Masjid al-Ikhlas in down-at-the-heels Newburgh in 2008. Mosque leaders say he would meet congregants in the parking lot afterward, offering gifts and telling them they could make a lot of money–$25,000–if they helped him pursue jihad. The assistant imam said the suspicion Hussain was an informant was so great “it was almost like he had a neon sign on him.” A congregant told a reporter that, in retrospect, everyone wished they’d called him out or turned him in. “Maybe the mistake we made was that we didn’t report him,” the man said. “But how are we going to report the government agent to the government?”

Hussain bought meals for the group of four men he assembled because none of them had jobs or money. The owner of a Newburgh restaurant where they occasionally ate considered him “the boss,” because he would pick up the tab. Among his other inducements were the offer of $250,000 and a BMW to the most volubly anti-Semitic plotter, the man the government says was the ringleader, James Cromitie. To drive that car, Cromitie would have needed a driver’s license–which he didn’t have. Another supposed plotter, a Haitian, was a paranoid schizophrenic (according to his imam), which was the reason his deportation had been deferred (according to The Nation’s TomDispatch.com), and who kept bottles of urine in his squalid apartment (according to the New York Times). The last two, both surnamed Williams, have histories of drug busts and minimum-wage jobs in Newburgh. At trial the government asserted that the plot was driven by anti-American hatred. But in papers filed in court by defense lawyers before the trial began, Cromitie is quoted in government transcripts explaining to Hussain that the men “will do it for the money. … They’re not even thinking about the cause.”

Hussain supplied his motley crew with two bogus bombs assembled for him by the government–lots of wires and timers, but harmless. He took them to Connecticut to show them a Stinger missile (disabled by the FBI), which they might use to bring down planes at Stewart Air National Guard Base. Court testimony showed that when Cromitie tried to back out, saying he didn’t want to hurt any women or children, Hussain badgered him, saying he was putting Hussain’s reputation at risk. The FBI paid Hussain nearly $100,000 for his efforts.

The arrest of the Newburgh Four was choreographed to perfection. A police helicopter shot live video as Hussain drove them down the Saw Mill River Parkway. After he and the four others left fake bombs at the Riverdale Temple and Riverdale Jewish Center, located about a block from each other, a massive police presence revealed itself: a special semi-rig sealed off one end of the street and an armored truck the other; and a slew of plainclothes officers descended on the suspects, guns drawn, breaking their SUV’s windows and pulling the men out. Within an hour, Mayor Michael Bloomberg, Police Chief Ray Kelly, and local elected and police officials were on the scene and in front of the television cameras, praising the capture of the dangerous criminals and the aversion of what, in the mayor’s words, “could have been a terrible event in our city.” A law enforcement official assured citizens that the men’s actions “had been fully controlled at all times.”

Which seems like an understatement. The government played the men like marionettes. Apparentlly, they knew nothing about how informants like Hussain have set up other sad-sack would-be bad guys like them. Other cases include those of the Liberty City Seven, a group of semi-homeless men in Florida who, with government encouragement, conspired to blow up the Sears Tower in Chicago; and the Fort Dix Six, whose scheme to attack Fort Dix in New Jersey depended on directions from a laminated pizza delivery map.

No one will argue that the Riverdale accused are nice people. James Cromitie is particularly unattractive; he was secretly recorded many times wishing death upon Jews. But America has a lot of haters, and thinking bad thoughts is different from initiating steps to act on them. At the two-month trial at federal court in Manhattan that ended with convictions on Oct. 18, defense lawyers argued entrapment, saying that their clients were not predisposed to terrorist murder; rather it was Hussain’s planning, encouragement, and offers of money that got them to join his jihad.

But the entrapment defense has failed in each of the 30-plus terrorism prosecutions involving an informant since 9/11, according to Karen Greenberg of NYU’s Center on Law and Security, who attended the men’s trial. Of the Bronx prosecution, she told the New York Times, “If this wasn’t an entrapment case, then we’re not going to see an entrapment case in a terrorism trial.” Entrapment is famously difficult to prove–the burden is on the defense, which must typically address various questions around predisposition to commit the crime, such as who purchased the weapons? Who came up with the plot? Who selected the target? Who chose the co-conspirators?

In a trial like that of the Newburgh Four, in which the defendants were charged with terrorism, Greenberg told me, the defense should raise questions about the conspiracy’s ideological roots: Who suggested an interpretation of Islam which promoted jihad? Who suggested working with Lashkar-e-Taiba? (as the defendants thought they were doing, via Hussain). Jurors also need to understand that anti-Semitic speech is different from terrorist conspiracy.

Since legal scholars agree that the entrapment defense is a key buttress against an overstepping government, its hopelessness in these cases would appear to challenge the legitimacy of the government’s informant-driven war against homegrown terror. In Greenberg’s opinion, it would also suggest that the legal definition needs to be re-examined. “I’m talking philosophically,” she says, but the repeated ineffectiveness of the defense “would suggest it might be something that the [legal] profession as a whole wants to consider.” This particularly applies in the current climate, where terrorism suspects are “guilty until proven guilty.”

And what’s with targeting all these mosques? Jon Sherman, a lawyer who authored an influential paper on entrapment last year, believes that “we are throwing way more resources at homegrown terrorism in Muslim communities than we are in poor and disaffected communities that support militia groups in places like Ohio and Tennessee and Michigan. … [I]f you put the same effort into infiltrating those communities with undercover informants, you might make as many cases if not more.” James J. Wedick, a 35-year retired veteran of the FBI who has testified for the defense in terrorism cases, similarly told BusinessWeek this fall that since 9/11, there has been “aggressive use of paying individuals large sums of money to go into small ethnic communities and look for individuals who are interested in harming the country.” He questioned whether the strategy was likely to net terrorists, or “people who have mental problems and wonder what it would be like to blow up the Sears Tower but they can’t get out of bed in the morning.”

This prong of our nation’s anti-terrorism strategy seems tantamount to sending lots of little devils out into Muslim communities and getting them to sit on people’s shoulders and whisper in their ears. One imagines that there is no shortage of Americans who, with enough money and other enticement, could be lured into crimes either ordinary or political: selling drugs or attacking gay people or racial minorities. But does dangling carrots that reward badness really make us safer? If it hadn’t been for the FBI, I don’t believe the Newburgh Four would have targeted my neighborhood, or anyone else’s.